Melbourne University Press has bucked the “woke” trend and published a book on the founder of the Liberal Party, Sir Robert Menzies.

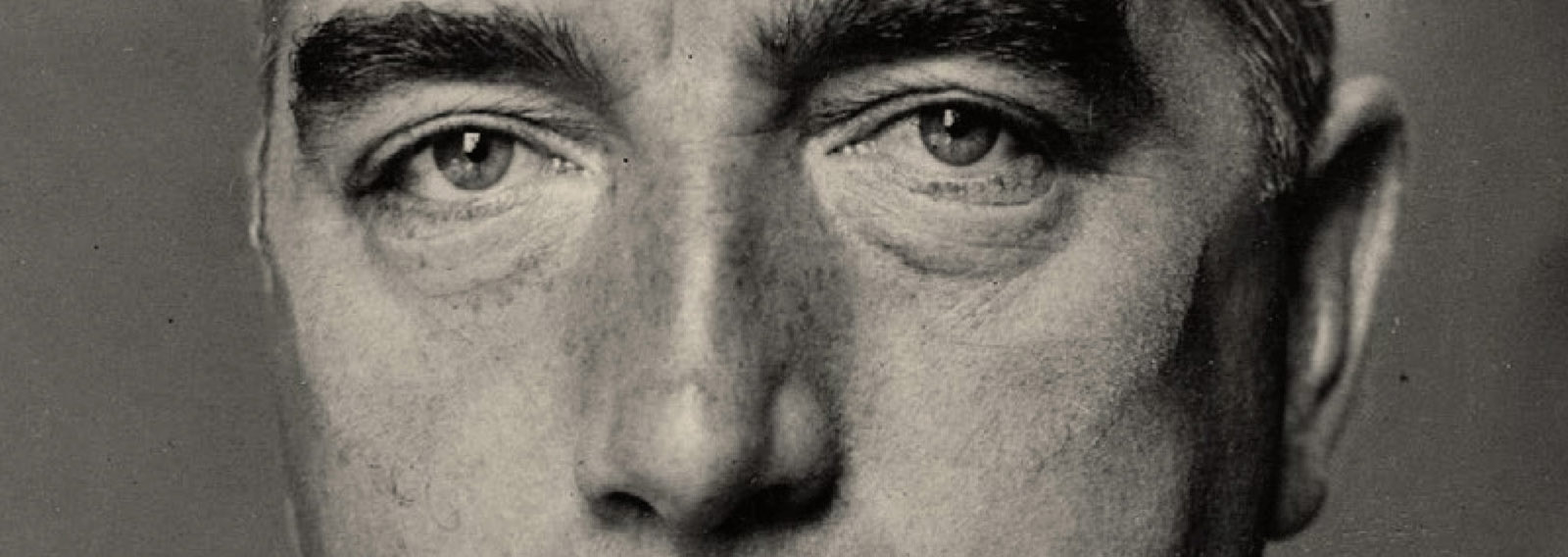

‘The Forgotten Menzies’ is a window into the soul of a steadfast Australian political icon.

Authors Stephen Chavura and Greg Melleuish deliver a short history of what made Menzies a monumental force in Australian politics.

They retrieve the memory of a leader who believed in Australia, the character of its people, the strength of its heritage, the life-sustaining momentum of its Biblical Christian values, and the potential these still offer to all Australians.

‘The Forgotten Menzies’ is a timely reminder about the role of good government in an era desperately in need of conviction politicians, and straight-talking leaders, not (to quote Janet Albrechtsen), ‘therapists fretting about our feelings.’

Remembered as one of Australia’s longest-serving Prime Ministers, it’s Menzies’ decision to sell pig iron (scrap metal) to Japan in 1938, that most Australians remember about him.

This is thanks to triggered trade unionists who’d baptised him, “Pig Iron Bob.”

The Dalfram dispute, as it is called, was a politically motivated protest against government laws regulating Union control over dock workers.

Amplifying the pathos was anxiety about Japanese militant expansionism. The sale of Australian pig iron to Japan appeared to be helping Japan prepare for war. The Imperial Japanese military’s ‘rape of Nanjing’, in China, 1937, exacerbated the concern. Menzies’ political opponents were well-armed.

At that time Australia was still isolated from Japan’s war ambitions. The Imperial Japanese weren’t considered a threat to Australia or the Pacific; a fact backed by the surprise attack on Pearl Harbour, and later Darwin.

Consequently, Menzies, then the attorney general, was more concerned with stopping the Unions setting a precedent, whereby they ‘could dictate Australian foreign policy’, than he was the Imperial Japanese making armaments.

Nevertheless, for the general public, “Pig Iron Bob” stuck.

So did the stigmatism that implied Menzies helped arm the Imperial Japanese. It’s why I remember my father, and his father, both lifelong Labor voters, always referring to Menzies with disdain.

Talk to my mother about him, and you’ll receive the quick, sharp, mocking reply, “oh, you mean Pig Iron Bob?” (Bold font. Exclamation mark. Exclamation mark…)

The closest ‘The Forgotten Menzies’ comes to talking about this, is a brief remark acknowledging Labor mythology. It didn’t go into it, because Chavura and Melleuish didn’t have to. Their unpacking of Menzies the man, and Menzies the politician, challenges Menzies the myth.

It separates the real from the mythical, unchaining the real Menzies from the hated straw man.

Chavura and Melleuish convincingly argue that Menzies is best defined as a ‘cultural puritan’ (p.79). He wasn’t strictly a conservative, but a believer in the principle that ‘good government went beyond ideology’ (p.9).

Menzies held to the belief that “Britishness” – British ideals built on the Protestant faith such as ‘sturdy independence, the sanctity of domesticity, labour, thrift’, and a civic-minded sense of duty towards God and others – should aspire Australians to be ‘lifters not leaners’ (pp.40, 59, 65 & 84).

This starts at home, ‘the great school and training ground of citizenship.’ (p.51). Forged on the question: “How can I qualify my son to help society?” Not, “How can I qualify society to help my son?” (p.65)

The foundation for this British idealism is the often-misunderstood Puritans (pp.56 & 72). Seen in the concept of the ‘sturdy yeoman’; whereby ‘individuals should behave independently, but that did not mean extreme individualism or licence.’ (p.23)

In purely Puritan terms this is the lived-out emancipation of the Gospel: Christ sets us free to be free from sin, not free to sin. Costly grace vs. cheap grace. Lifting and being lifted, as opposed to leaning and dragging down.

Or as Dallas Willard penned it, ‘grace is opposed to earning, not to effort.’

Cultural Puritanism was about rights and responsibilities (p.74), free of ‘the vast public utility’, and the ‘idle false doctrine that the Government owes us everything.’ (p.73)

An ideal expressed by Richard Baxter’s theme in the Puritan classic, ‘The Reformed Pastor’ as grace walking hand-in-hand with self-denial. The latter always a secondary act; a response to God’s primary “yes and no” actualised through God’s covenant with Israel and revelation in Jesus Christ.

As is evident by the content of Menzies ‘The Forgotten People’ speech of 1942, his political platform supported mutual reciprocity built on responsible freedom, frugality, and industry.

With this, asserts Chavura and Melleuish, Menzies firmly believed in a hand-up, not a hand-out.

He wasn’t a ‘utilitarian’ or materialist. Instead, he advocated an economic middle ground between ‘selfish laissez-faire capitalism and suffocating state socialism’ (pp.70 & 85).

If I’ve understood Chavura and Melleuish properly, Menzies tried to build a bridge between the old world and the new.

His desire to see the best of that old world preserved in the new failed to find traction in a rapidly changing world. At best he could be labelled naïve, and sentimental, but it would be reckless to dismiss Menzies’ example, and general ideas as outdated and irrelevant to us today.

‘The Forgotten Menzies’ portrays a fallible man who strongly believed in Australians, its rich heritage, and its future (p.130).

Menzies’ critics see the former Prime Minister as a fossilised leftover of a by-gone-era. A leader who held Australia back from its coming of age. Stopping it from finding its own cultural identity as the nation matured beyond the Britishness that gave Australia life.

Chavura and Melleuish challenge this with the reminder that what Menzies held to, and what made him, still exists in the fabric that holds up the corridors of Australian institutions.

‘The Forgotten Menzies’ is an academic text, but don’t let this dampen your interest. Its sober rhythm and well-argued propositions retrieve Menzies from the museum, and challenge readers to seek out a place of relevance for him in contemporary Australian society.

For me the importance of this book is its liberating of the real Menzies from the “Pig Iron Bob” fallacy.

Its only weakness is that its authors don’t seem to be aware of the significance of the treasure they’ve uncovered. This seems to have been overlooked by a careful concern for whispered applause, and a critic-appealing lament that portrays Menzies as a tragic figure, who failed to move with the times.

The strength of the ‘The Forgotten Menzies’ isn’t just that it rescues Menzies from the museum, it shines a spotlight on cultural Puritanism and with it the blessing of Australia’s inherent “Britishness”.

Thus, prompting the reader to ask whether or not cultural Puritan independence might provide a resolute alternative to joyless Cultural Marxist dependency on big government.

For example, Menzies’s rebuke of those who would divide Australia by class hatred applies to Critical Race and Queer theory’s subdivision of Australians into an oppressor vs. oppressed category based on identity politics and its intersectional rubric.

‘The only true classes in Australia are the active and the idle’ (p.97).

Add onto this the implications of Menzies’ defence for private religious education alongside public, and there’s a strong foundation for rejecting what A.W Tozer called the secularisation of the sacred.

Menzies speaks directly to the erosion of Church and State by radical Leftists who yell out demands for the state to reach into the Church.

‘The Forgotten Menzies’ is a positive step towards ensuring that Menzies and the good that he stood for is not forgotten.

Chavura and Melleuish’s next book should be Menzies vs. Marx.

[i] Chavura, S.A, & Melleuish, G. 2021. The Forgotten Menzies: The World Picture of Australia’s Longest Serving Prime Minister, Melbourne University Press

[ii] Tozer, A.W. 1966. Man: The Dwelling Place of God Authentic Publisher’s Ed. 2009 (p.52)