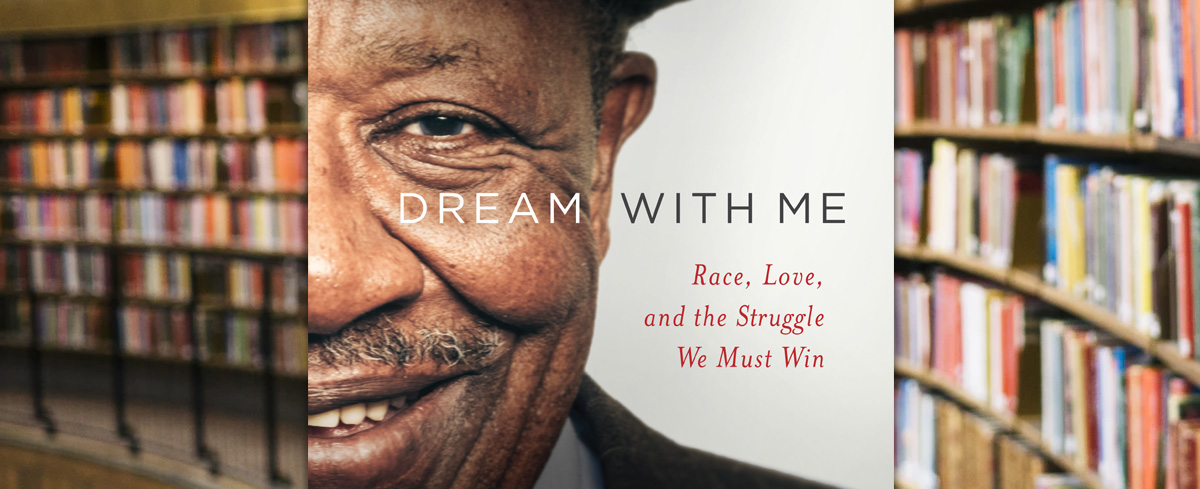

John M. Perkins is an American civil rights campaigner. His 2017 book, ‘Dream with Me’, is a brave step forward in seeking to create better dialogue between both black and white communities. Overall, ‘Dream With Me’ is a call for both black and white Americans to unite, in their diversity, under God. This review will focus on two primary strengths of Perkins’ work.

John M. Perkins is an American civil rights campaigner. His 2017 book, ‘Dream with Me’, is a brave step forward in seeking to create better dialogue between both black and white communities. Overall, ‘Dream With Me’ is a call for both black and white Americans to unite, in their diversity, under God. This review will focus on two primary strengths of Perkins’ work.

The first strength is the presence of a Theology of Christian Liberation. Perkins refuses to take the easy path of perpetual anger, condescension and resentment – both traits found in Black liberation theology (which is largely tainted by Marxism). Instead, Perkins leans towards the rules of solidarity[note]Defined as proactive empathy, as opposed to the spectator-sympathy.[/note] and subsidiarity.[note]Community and government groups play an auxiliary role in supporting initiatives; helping, not controlling or taking away individual responsibility; ergo offering a hand-up, not a hand out.[/note] In doing so, he proclaims a social doctrine, not the social gospel.[note]Teachers about Jesus’ teaching, not about Jesus Christ; turning Christianity into a list of ethical principles. In effect, Christless Christianity e.g.: “Who needs Christ? If I follow his example by being a good person, then I’ll be able to save myself, make God happy and get into heaven.”[/note]

The significance of this distinction is, in the former, Jesus Christ remains at the core of the gospel and isn’t replaced by attempts (found in the latter) to synchronise Karl Marx with Jesus Christ.[note]See Jacques Ellul’s brilliant criticism in Jesus & Marx, 1988.[/note] In addition, a social doctrine allows the freedom to affirm and critique the issues impartially. The social doctrine, in this context, is greater than the social gospel, because the Gospel remains free of any ideological lens (particularly atheist and theistic Marxism). The Gospel (read Jesus Christ) is allowed to speak for Himself without being muffled by Marx.

Unlike the social gospel, which tends to ‘stray from Scripture’ (D. Bonhoeffer[note]‘The contempt for theology is outrageous. Rauschenbusch’s own “theology for the social gospel” clearly shows, like its successors, that a lack of obedience to Scripture is characteristic for the teaching of the social gospel.’

(Bonhoeffer, DBW 12, Memorandum: The Social Gospel, p.242)[/note]), Perkins’ social doctrine doesn’t respond to injustice through a lens of victimisation, double-standards, excessive-unbridled egalitarianism (dismissive tolerance and irrational equality), dependency on the state, or entitlement. He, instead, advocates for a ‘new alternative’,[note]Perkins, J.M 2017 Dream With Me: Race, Love, and the Struggle We Must Win, Baker Publishing Group, (p.85)[/note] building on what he calls the ‘three R’s’: ‘relocation, reconciliation and redistribution.’(p.88) Here, Perkins upholds the uniqueness of Christian liberation, which holds to God’s liberation of humanity from slavery to sin.[note]Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, 1984, Instruction on Certain aspects of the Theology of Liberation, (Source)[/note]

‘White people need to take responsibility for centuries of imperialism and failing to repent, but black people also need to take some responsibility for the breakdown of our families (p.70) […] Things only get fixed – truly fixed – when they are mended by God through faith. Often we have it backwards trying to fix things for God rather than letting God fix things through us (p.81).

The secondary strength of ‘Dream With Me’ is that Perkins doesn’t sugar coat reality. He’s up front about racism, the impoverishment of some Americans (in general),[note]‘To be honest, I had never given a second thought to poor whites. I still regarded them negatively – as redneck, trailer park white trash. The wealthy white people could help me, but what good were the poor whites to me? But then this poor white couple showed up at my doorstep. My automatic response was to treat them the way whites had treated poor blacks – to patronize them. But these people were teaching me, John Perkins, the guy who was supposed to be leading the church in reconciliation; a lesson in what it really means to be reconciled to one another.’ (pp.56-57)[/note] and is outspoken in his call for the renewal of efforts that move America towards justice;[note]‘Justice is an act of reconciliation that restores any part of God’s creation its original intent, purpose, or image’ (p.207)[/note] towards lived reconciliation. Such a lived reconciliation will require jettisoning the shackles of identity politics.

For Perkins, progress towards this goal involves reclaiming the word reconciliation. Perkins believes that

‘‘Issues related to ethnicity and tribalism may divide us, but we are one race – the human race (p.54) […] we have taken God’s definition of reconciliation and made room for bigotry by inserting race into the concept. Racial reconciliation is not a biblical term. People use race as a slave master.’ (p.84)

What he calls for instead is a reconciliation firmly grounded in God’s reconciliation of the sinner to Himself.

‘I will call for – what I believe the gospel calls for – unity across ethnic and cultural barriers’ (ibid)

Perkins’ quest is to attain genuine equality (as opposed to any false utopian idea of supremacy[note]‘Wealthy whites also used the poor whites as tools of oppression — having blacks beneath [poor white folks] made those [folks] feel superior.’ (p.60)[/note] or the fool’s quest of seeking perpetual payback, in order to make things equal). He is adamant that Americans should build on the faith, approach and doctrine of the early civil rights campaigners. This road is difficult, but it should, and must be travelled.

Perkins offers no instant-fix formulas. What he does offer is a roadmap for how this can be achieved. At the heart of ‘Dream With Me’ are ‘the three R’s: these are relocation where the old informs the new; reconciliation, free of victimization and identity politics; redistribution, not of wealth, but of opportunity’ (pp.74-89). What Perkins means by relocation is a readiness to be available; a readiness to be where, and to do, what God has called the individual to. Redistribution is about ‘stewardship’[note]‘We’ve gotten away from the understanding that all of resources belong to God, and that we are stewards of whatever portion of those resources He has entrusted us with.’ (p.85)[/note] (p.85) and reconciliation ‘is a way of life that displays God’s redemptive power’ (p.84).

‘Dream With Me’ is a careful discussion about the issues that face African-Americans. Perkins acknowledges (with great care) the historical wrongs suffered by African-Americans at hands of racial hatred. He acknowledges historical abuses by returning to his own experiences. Referring to his own suffering, Perkins sets the example:

‘On February 7, 1970, while I lay on the floor of the Simpson County Jail in Brandon, I made the decision to preach a gospel stronger than my racial identity and bigger than the segregation around me.’ (p.56)

‘Dream With Me’ brings the civil rights movement out of the museum, and it takes reconciliation out of the hands of race baiters, who seek to keep African-Americans down purely for political advantage. ‘Dream With Me’ challenges the status quo of racial divisions by inviting change through humility and understanding.

Perkins doesn’t play the blame game. He seeks to end the cycle of abuse by encouraging others to not engage in reciprocating stale responses veiled by resentment and forced tolerance, all of which are underpinned by unrepentant hearts, pride and a fraudulent reconciliation, grounded in toxic identity politics.

In sum, ‘Dream With Me’ brings the practice of reconciliation to life. Perkins provides a viable way forward. This is a brave book written by an elder in the Civil Rights movement. Whether Americans can move beyond stale cultural slogans and tribal segregation; beyond blame and shame,[note]‘…we need to start getting beyond this stuff. Issues related to ethnicity and tribalism may divide us, but we have to start recognizing that we are one race – the human race’ (p.54)[/note] is an open question. It’s one that can only be answered when and where people are freed from the prison of ‘isms’ – racism, sexism, ageism, classism, and so many other divisive systems’ (p.50)

This book is for anyone who has been dealt blows by the hands of injustice, ostracism, abuse and uncalled for hostility. It’s for those who want to move beyond the logical fallacies which manipulatively assume that because someone has a certain type of skin colour, their melanin predetermines their heart, character and how they view the world around them; for those who want to keep Jesus Christ at the centre of justice, reconciliation and stewardship toward our neighbour.

‘Dream With Me’ is a call to prayer-filled action, which falls in line with Paul the apostle’s command and prayer for the Church in Corinth: ‘aim for restoration.’ (2 Cor. 13:9 & 11, ESV)[note]Disclaimer: I did not receive any remuneration for this review, in any form.[/note]