Details about Simone Weil’s life and thought are enigmatic. Other than what’s included in the general encyclopedic biographies circling the internet, I know very little about her. Unlike someone such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, there is no long, authorised biography written by her friends. What knowledge I have been about to find out about her, is padded by what I’ve learnt from conversations with internet friends, whose admiration for her work has increased over the years.

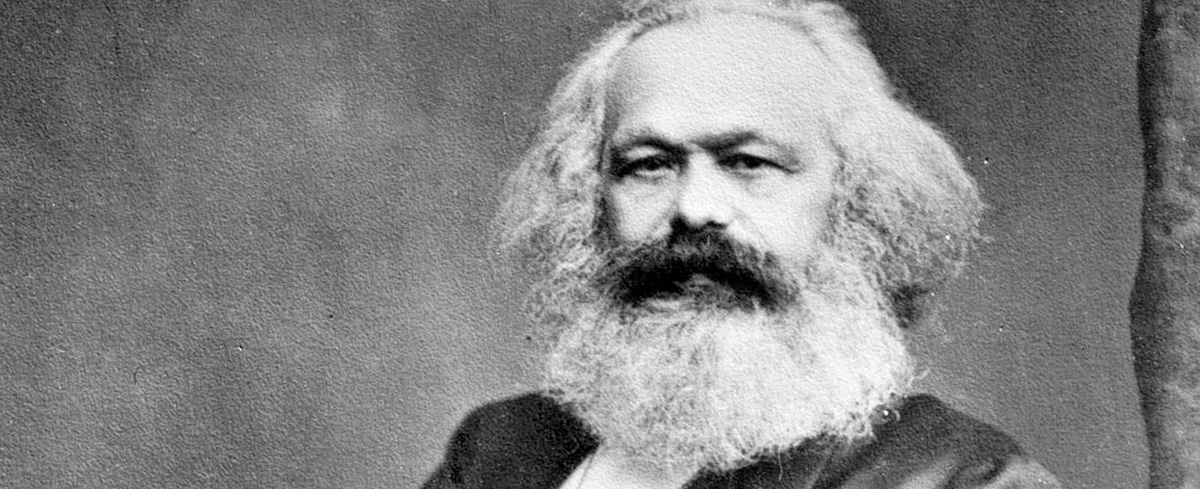

Simone was a French intellectual. Like Jacques Ellul, Weil worked in the French resistance, was an admirer of Karl Marx, and a contemporary of Albert Camus.

Weil moved back towards Roman Catholic Christianity and took an interest in Catholic mysticism. This detached her from the French intellectual trends of her day. Weil also made a break with Marxism. Whilst Weil remained a fan of Karl Marx, alongside her criticism of [crony] capitalism, she also wielded a heated criticism of Marxism.

Some of these criticisms are set out in Oppression & Liberty, 1955. Weil’s major criticisms begin with the monopoly of centralisation. This is what Weil says fuels forms of ‘bureaucratic oppression’ from a ‘bureaucratic caste’[note]Weil, S. 1955, Oppression & Liberty, 2001. Routledge Classics, ‘the dictatorship of the bureaucratic caste’ (p.14)[/note]:

‘All exclusive, uncontrolled power becomes oppressive in the hands of those who have the monopoly of it… instead of a clash of contrary opinions, we end up with an “official opinion” from which no one would be able to deviate.’ (pp.15 & 16)

Three bureaucracies exist: these are ‘state, capital industries and worker’s organisations (trade-unions)’ (p.17). Given the right environment (such as Germany in the 1930s) all three can merge into one. The state takes control of the market and runs it from a centralised politick, with a salaried and bureaucratic hierarchy. Weil calls this ‘state capitalism[note]Weil credits Ferdinand Fried with the term and its definition.[/note]’. This means that the economy is managed by the government and government approved capital industries. In 1930’s Germany, this manifested as a dictatorship resting on the twin supports of trade unions and the national-socialist movement[note]An interesting add-on to this is Weil’s statement: ‘The communists accuse the social-democrats of being the “quartermaster-sergeants of fascism”, and they are absolutely right.’ (p.27)[/note]’ (p.25).

The zenith of all of Weil’s criticisms is when she calls Marxism ‘a fully-fledged religion in the impurest sense of the word’ (p.165). Two other earlier statements back this up: ‘‘Marxism is the highest spiritual expression of bourgeois society’ (p.124); ‘Marxism is a badly constructed religion; it has always possessed a religious character’ (p.154).

In a similar way to Jacques Ellul, Weil advocates the truth in Marx’s critique, but is not a believer in Marxism. For her, the social, economic and political mechanisms of bureaucracy and industry, turn men and women (the working class), into machines. The working class becomes a means to an end.

Weil’s praise for Marx doesn’t go any further than this:

the truth in Marx’s critique is found in how he ‘defined with admirable precision the relationships of force in society […] Two things in Marx are solid and indestructible. First: method; study of and defining the relationships of force. Second is the analysis of Capitalist society as it existed in the 19th Century – where it was believed that in industrial production lay the key to human progress ’ (p.152).

Weil’s short lived praise for Marx ends here: ‘Marx was an idolater; he idolised the Proletariat and considered himself to be their natural leader’ (p.151); Marx made oppression the central notion of his writings, but never attempted to analyse it. He never asked himself what oppression is’ (p.154)

Oppression & Liberty concludes with Weil’s summary of Marx’s failings. This includes his obsession[note]Ibid, (p.178)[/note] with production, class war and moralism.

‘The only form of war Marx takes into consideration is social war – (open or underground) – under the name of class struggle. Class struggle or social war is the sole principle for explaining history. Marx was incapable of any real effort of scientific thought, because that did not matter to him. All this materialist was interested in was justice. He took refuge in a dream and called it dialectical materialism.’ (pp.178 & 180)

As Weil explains,

‘Marx fell back into the ‘group morality which revolted him to the point of hating society. Like the feudal magnates of old, like the business men of his own day, he had built for himself a morality which placed above good and evil the activity of professional revolutionaries; the mechanism for producing paradise’ (p.182). Marx’s ‘moral failing was that he do not seek the source of the good in the place where it dwells.’ (p.183).

When I was given a copy of Oppression and Liberty, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I hadn’t planned on reading the book, but I’m thankful to have had the chance to make a careful study of it.

The subject matter is dense. This is made more complex by Weil’s writing style. However, this complexity doesn’t make Oppression & Liberty unbearable to read. Weil takes aim at a lot of relevant themes which pose serious questions for our contemporary setting. These themes include unintended consequences, ‘bureaucratic oppression’[note]‘the bureaucratic oppression; the bureaucratic machine’, (p.13)[/note], monopolies, power, materialism, group-think morality, sociopolitical force, the mechanisms of power, and subjectivism.

The latter coming out through her discussion and warning about seeking morality in places other than where genuine goodness and authentic morality dwells. This can be interpreted to mean that God is the only means by which humanity has a moral anchor. Weil’s example of this is Karl Marx and his obsession with justice, production and power. These led to contradictions in his theory and its application. His subsequent moral failing was that his quest for morality searched everywhere, but where the source of goodness and authentic morality is, can, and therefore, ought to be found.

Oppression & Liberty is a book that teaches something new each time it’s opened. Weil’s book is a gold mine, with a complex nature and a variety of themes which require careful navigation. Because of this it’s difficult to take ownership of Weil’s main points with just one reading.

Oppression & Liberty’s main theme pivots on an analysis of Karl Marx. Within this analysis, Weil yields a critique of Marxism. This criticism is balanced by her agreement and disagreement with Marx. For Weil, any centralised control of an economy (monopoly), leads to the oppression and tyrannical rule over those who work under it, or are made to serve it. In sum, this criticism states that despite appearances, Marxists, plutocrats and bureaucrats alike, all pose a threat to equity and morality.

The warning from Simone Weil in Oppression & Liberty is loud and clear: those who chose to entertain Marxism, big bureaucracy or crony capitalism, ride the backs of monsters.