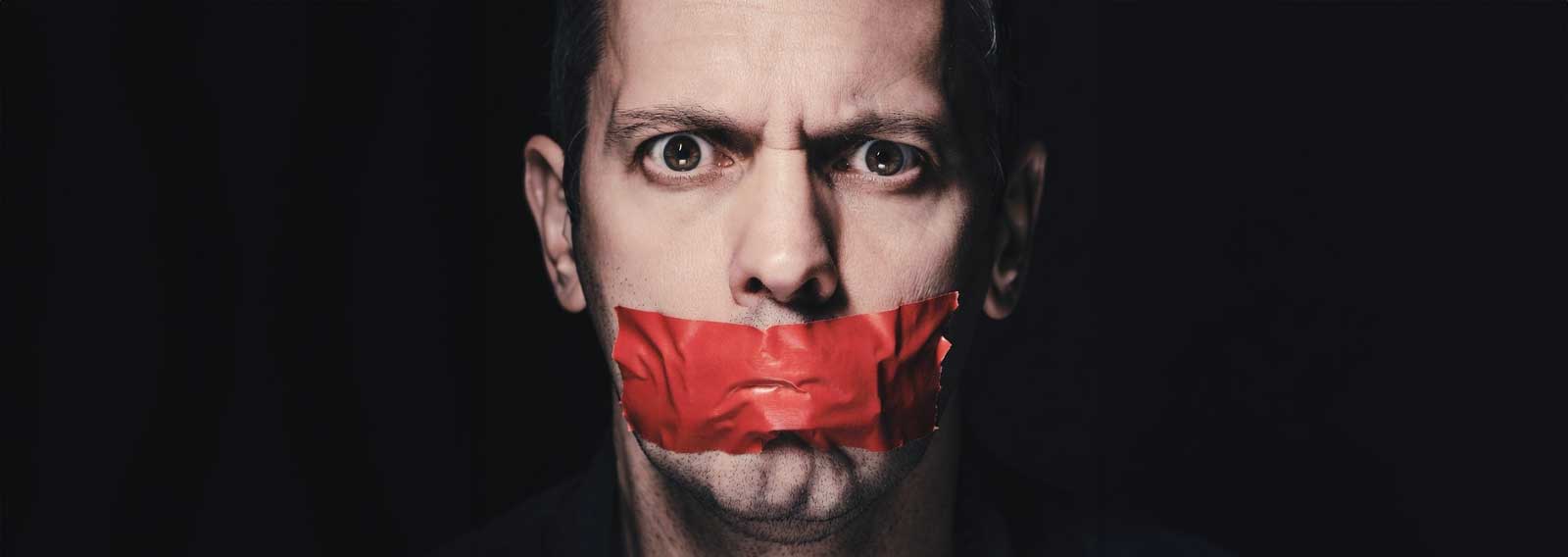

Today, we’re told that “offensive words,” ideas, or symbols must be curbed and criminalised to preserve “social harmony” and accommodate the sensitivities of diverse religious and cultural communities. When someone says or does something deemed “offensive,” our politicians often rush to condemn the act, as if the offender has violated some imagined right of others never to have their feelings hurt or their views challenged.

But there is no such thing as a “right not to be offended,” and more importantly, there cannot be. A right like that is impossible to define, impossible to police, and impossible to uphold. This is especially true in a so-called “multicultural society,” where competing and often contradictory moral frameworks inevitably clash over what counts as good, acceptable, or offensive.

Offence is, by nature, entirely subjective. What is deemed immoral and impure for one person might be morally neutral or even good to another. You could create a new religion tomorrow and declare public displays of the colour green forbidden; that doesn’t obligate the state to monitor everyone’s clothing simply because your followers claim to be offended.

If subjective offence became the measure of legality, there would be no limit to what people might demand be censored or banned. Every individual could set their own religious and emotional threshold as a public standard. Society would quickly become ungovernable. In other words, there cannot be a “right not to be offended,” because there is no limit to what might offend. The moment our politicians begin policing personal sensitivities, they open the door to endless grievances and limitless legislation—creating a system where, eventually, anything and everything could be deemed criminal.

This is precisely why free societies protect freedom itself, not everyone’s feelings. The moment personal sensitivities set the boundaries of speech and behaviour, freedom collapses into a system governed by the most easily offended. And, as the Western world is gradually discovering, usually by the most strategically offended.

Instead of curbing liberties to appease every possible grievance, we must rather preserve the space for people to speak, think, and live without being controlled by unlimited and undefinable standards. A free society depends on resilience, open debate, and the understanding that while offence is sometimes unavoidable, the alternative—silencing and censoring people to accommodate every imaginable discomfort—is far worse.