When we hear the phrase, ‘the Great Awakening,’ we think of some amazing religious revivals that occurred in America in the first half of the 1700s. But here I am using it in a more generic sense. That is, the events of 2020-2021 caused many people to wake from their slumber, rouse themselves out of their stupor, and really start questioning things, including the role and reach of the state.

How we should understand civil government in general, and a biblical text like Romans 13:1-7 in particular, both came into sharp focus during this time – and ever since then. While I had written often about statism and the rise of tyrannical government before, during the Covid reign of terror with all the lockdowns, medical fascism and violation of basic human rights and freedoms, I especially started discussing all this.

As but one indication of this, I just searched my site for the term ‘statism’. It is found in some 200 articles, with it first being used in 1992. But the bulk of the times it is used has been over the last four years or so. Thus my thinking and writing about the state, its limits, and its abuses, certainly came to the fore when the Covid virus broke out.

I was not alone during this period in starting to rethink things, question things, and revisit familiar texts such as Romans 13. So many other Christians did the same. One such person is an American pastor and New Testament professor, Timothy Decker. And his new book, A Revolutionary Reading of Romans 13 begins as did my article: by noting how Covid changed everything.

As he says in his Introduction, the pandemic caused him and other pastors to “take up matters of theology and passages of Scripture that have previously been left to minor significance.” Romans 13 is of course the main text he has in mind.

In short, he says that generally speaking we are to obey civil government, but there are many times when we are called to disobey. The commands found in Romans 13 must be seen in light of the totality of Scripture, as well as through the lens of the circumstances that existed when Paul wrote this epistle.

The historical and chronological situation must be kept in mind. There are two areas he dwells on in the opening chapters: the nature of the Roman government at the time, and the revolutionary zeal of some Jews living then. As to the former, Emperor Nero reigned from AD 54 to AD 68, dying at just 30 years of age.

Most Christians are aware of him as being an evil tyrant who mercilessly persecuted Christians. But as Decker reminds us, early on he was much less so, and only later did he become an arch-enemy of Christianity. He really only targeted them after the great fire of Rome in July of AD 64.

However, most scholars agree that Paul wrote Romans around AD 57-58. If he had written it later, would he have said things somewhat differently on this matter? What we do know is that the really hard-core persecution of Christians was not occurring in Rome when he did send his epistle.

The second point Decker wants to emphasise is the various revolutionary strands found among the Jews back then. We know about such things as the Jewish Revolt of BC 66–73. And in the gospels and the book of Acts we read more about such matters.

One of the disciples of Jesus was Simon the Zealot. The Zealots were a radical sect of Jewish patriots, or freedom fighters, committed to overthrowing Rome. And Barabbas for example was guilty of rebellion (“insurrection” ESV) and murder (Luke 23:19); while others such as Theudas and Judas had been dealt with by the authorities for their radicalism (Acts 5:36-37).

All these considerations must be taken into account as we try to get a handle on what exactly Paul is urging believers to do in Romans 13. By way of summary thus far, Decker says this:

If Christians, whether Jew or Gentile, were going to publicly preach and confess “Jesus is Lord” (which is tantamount to saying “Caesar is not”), then Rome may not have looked favorably on Christians, including Paul, who was seeking to make his way to Rome as a launching point. This is even more so if revolution and refusing to pay taxes were seen to be corresponding ideals. It seems, therefore, that Paul had ample reason to teach the believers at Rome that God has ordained the institution of human government – even Gentile ones – and if, in God’s providence, you live under such a government, you must submit to it rather than rebel against it in private revolution, as was the way of the zealots….

On the other hand, Paul also indicated that the civil magistrate, as God’s servant (Rom. 13:4), has a code of service he must live by. It seems to be that at the time Paul wrote Romans (around AD 56-58), the government in Rome was commendable in its God-ordained role of protecting its citizens and punishing the wicked. And to support and maintain such honourable practises, a Christian should not withhold taxes or other support. Indeed if God has instituted the civil magistrate’s role as protector, sporting such a noble endeavour is a good and moral act. As posted in Romans 13:5, this is a matter of the conscience that every Christian is duty-bound to believe. In that regard, taxation is not theft; it is a Christian’s response and responsibility to a government whom God has tasked to protect its citizenry.

Therefore, to squelch the common revolutionary spirit of the Jews in the first century, to teach against the false view that Christ as Lord means that Christians are not under the authority of a civil magistrate, to facilitate intra-church unity at Rome among various political positions (either for or against Rome), Paul inserted Romans 13:1-7 as part of his exhortation to the believers to reprove them of any notions of private revolution against Rome as well as to instil in them the doctrine of the God-created sphere of human government.

pp. 43-44

Now all this is found in the opening chapters of the book. In the next five chapters, he looks even more closely at what Rom. 13 is seeking to say. This includes an exegetical exposition of these verses. The final two chapters seek to tie all this together.

For example, Chapter 9 looks at a biblical definition of tyranny. Decker looks at possible definitions, and then lists these identifying parameters of tyranny:

- Rule without law or against current laws

- People forced the sin against God either by omission or Commission

- Overreach of sphere of sovereignty

- Law of special interest 1: law equally created or enforced upon those being ruled

- Law of special interest 2: law and equally created or imposed upon the ruler(s)

- Despotism: the gathering and accumulation of power

- Creation of immoral law that is either legislated, executed, or adjudicated

- Creation and enforcement of arbitrary law

- Commandment to disobey conscience

- Totalitarian control in the state’s desire to achieve a pragmatic utopia (p. 173)

He offers past and present examples of this, including so many of the things we witnessed during the draconian Covid lockdowns and human rights abuses. He also looks at biblical examples, including the Hebrew midwives disobeying Pharaoh, and Nathan the Prophet rebuking King David.

He reminds us of how Paul appealed to his rights as a Roman citizen when he felt he was being unjustly accused and treated (Acts 22:25-29). Decker offers several lessons from Paul standing against the leaders of the day:

First of all, we see how easy it is for magistrates and those tasked with enforcing law and punishment to be carried away by the sentiments of a mob….

Next, we see what it looks like when magistrates follow the law on the books….

Finally, we have a biblical example of a Christian who used and asserted the rights to him within his earthly citizenship….

We must conclude from Acts 22 that Paul’s actions are in no way a violation of Romans 13. It is not an error for Christians to demand that their civil governments keep true to its law and properly carry out its duties toward its citizens. (pp. 175-176)

He concludes the chapter by mentioning passages such as Proverbs 16:12: “It is an abomination to kings to do evil, for the throne is established by righteousness.” He writes: “A Christian is in proper submission to the civil magistrate even when passively resisting tyranny. And if that tyrant becomes ever more violent, a Christian has every reason and biblical sanction to actively resist with a magistrate-led revolt, providing the leader is a properly appointed magistrate and therefore possesses a duty to intercede.” (p. 205)

Here of course he is sharing the long-held understanding of the role the “lesser magistrate” in resisting tyranny. See more on that matter here.

His last main chapter offers current-day application and looks further at what transpired during the Covid wars. For example, in many jurisdictions, the churches were ordered to shut down and not have public worship services. Some church leaders resisted these edicts while far too many sheepishly complied.

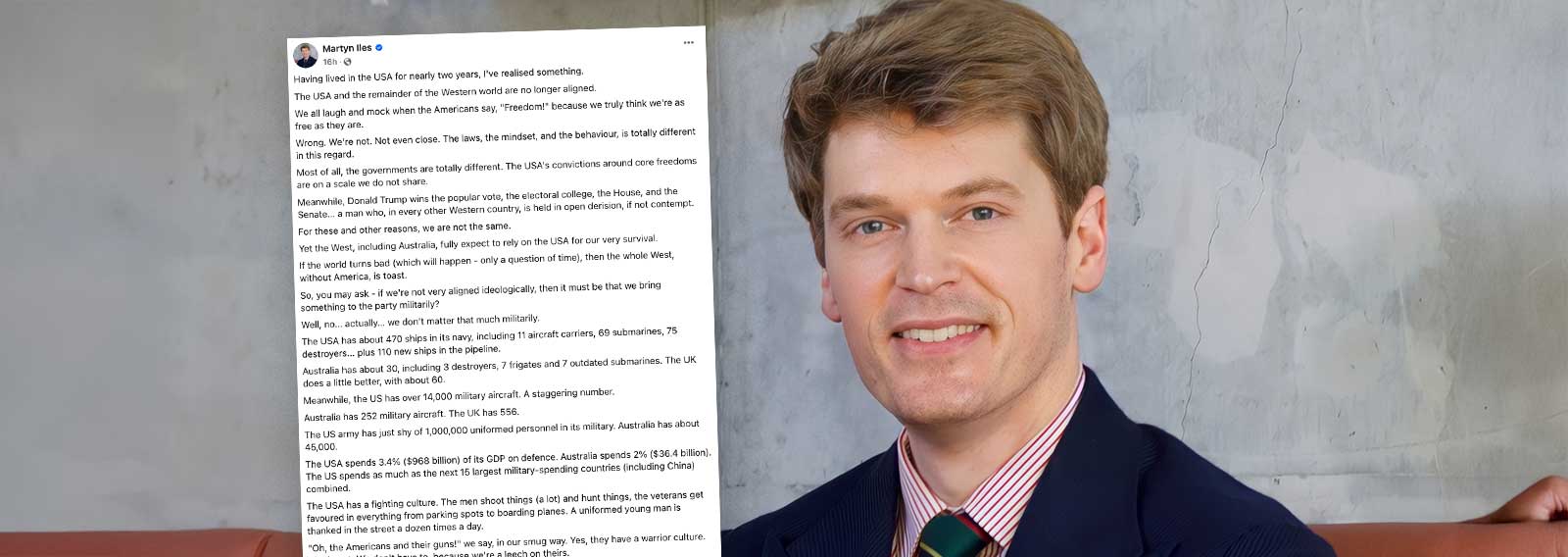

The picture I have chosen to use here shows Pastor Tim Stephens of Fairview Baptist Church in Calgary being arrested in May 2021 for daring to keep his church open. Another pastor from Calgary who was also arrested at this time – Artur Pawlowski – I wrote about in this article.

Decker looks at other such situations, and says this near the end of the book:

In Romans 13, Paul is arguing that the state or civil government is a biblically sanctioned institution. He is not saying how Christians are to live before or submit to that institution except that we are to not revolt against it in private revolution but are, instead, to support it and submit to it as legitimate sphere of authority handed down from God, insofar as it fulfils its God-ordained function. This careful distinction about Romans 13, that Paul primarily argues that the institution of government exists but not how we should exist under it, allows the necessary theological and practical qualifications that must be granted if we are to harmonise the many other passages of Scripture that regulate the proper occasions for resistance against government. It also means that Romans 13 cannot be used as a one-size-fits-all application to modern political squabbles. Instead, Christians must think wholistically of the Bible when reading and using Romans 13. They must think theologically of the doctrines it teaches.

p. 214

Heavy-duty issues like this will always raise even more questions for the Christian, and no small amount of disagreement in places will arise. However, as Decker says, this portion of Scripture is laying out broad principles, and not offering us a fool-proof detailed discussion of how it always can and should be applied. Wisdom and prayer are still needed.

And if Covid taught us anything, such wisdom and prayer are needed now more than ever.