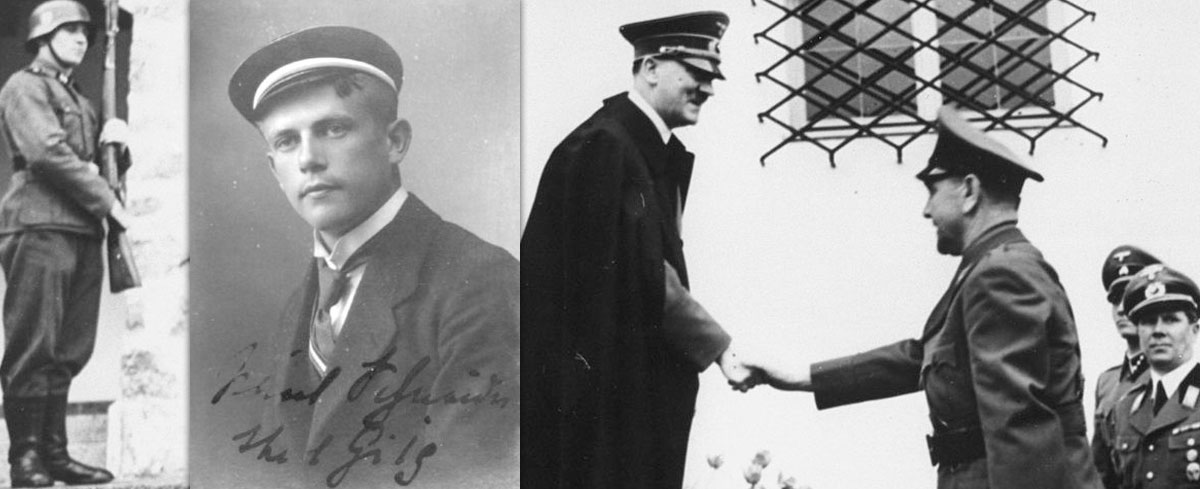

Arrested four times, Paul Schneider became one of the first theologians of the Confessing Church to be murdered by the Nazis, and the first protestant pastor to die in a Nazi concentration camp.

In a nut shell, Schneider was labelled a firebrand. Like a lot of the Confessing Church Pastors and theologians, his theological resistance was “politically incorrect”.

His defiance was a veritable revolt against ‘compromise with Nazi ideology, and the indifference of the people.'[note]Stroud, D. (ed.) 2013 Preaching in Hitler’s Shadow: Sermons of Resistance, Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing p.75[/note]

As a result the ‘terror state would forbid him to preach, and attempt to silence his opposition by enforcing a form of exile’[note]Ibid, p.94[/note]. Schneider was later arrested and imprisoned.

His tenacity is evidenced by accounts such as this:

In January 1939 two prisoners who tried to escape were hanged in front of the assembled inmates. Paul Schneider called out through his cell window: ‘In the name of Jesus Christ, I witness against the murder of these prisoners…The response was another twenty-five lashes.

Greg Slingerland narrates the scene brilliantly:

On a January morning in 1939 in the concentration camp of Buchenwald, two beleaguered prisoners who had attempted to escape were brought into the parade grounds of the camp. There they were mercilessly executed. As the bodies of the two prisoners went limp, a voice rang out across the camp from the window of the punishment cell.

“In the name of Jesus Christ, I witness against the murder of these prisoners!”

Not quite six months later, Schneider, beaten and starved, was euthanized by the Buchenwald camp doctor. Schneider was survived by his wife, Margarete and their six children.

Along with Schneider’s outspoken preaching in prison, his theologically informed political defiance permeated his sermons.

The first in 1934, where he firmly asserts a theological critique against the ideology of the day:

We have tolerated the teachings of Balak (Numbers 22.6), of liberalism that praises goodness and freedom of men and women while minimising the honour of God and letting the seriousness of eternity fade away into a misty haze[note]Given the content, what he means here is a view of freedom without responsibility; power without accountability; denial of the transcendent.[/note]…we cannot close our eyes to the high storm-waves we see surging toward our people in the Third Reich’[note]Ibid, p.80 (Schneider)[/note]

The other is in a sermon smuggled out of a Gestapo prison camp in 1937 entitled: ‘About Giving Thanks in the Third Reich’. He draws deliberately on ‘Belshazzar, a poem written by Heinrich Heine, a 19th century German Jewish poet[note]Ibid, p.96 (Schneider)[/note].’

Schneider matches the attitudes of late 1930’s Germany with the attitude of ‘the Babylonian ruler, who fully ripened in his godless, proud, and wasteful misuse of God’s gifts, had drunk himself sick and mocked God.'[note]Ibid, p.104 (Schneider)[/note] (Daniel 5:13-30)

…His face is flushed, his cheeks aglow, till a sinful challenge to God resounds.

He boasts and blasphemes against the Lord, to the roaring cheers of his servile horde…

“Jehovah, your power is past and gone – I am the King of Babylon”

But scarce the awful word was said, the King was stricken with secret dread.

The raucous laughter silent falls, it is suddenly still in the echoing halls.

And see!

As if on the wall’s white space, a human hand began to trace.

Writing and writing across the stone, letters of fire, wrote, and was gone

The King sat still, with staring gaze, his knees were water, ashen his face.

Fear chilled the vassals to the bone, fixed they sat and gave no tone.

Wise men came, but none was equipped, to read the sense of the fiery script.

Before the sun could rise again, Belshazzar by his men was slain.

Dean Stroud notes: “Schneider no longer believed that ‘’our evangelical church” (read German Evangelical [Free] Church) could avoid direct conflict with the Nazi state.”[note]Ibid, p.76[/note]

For the Church in the West, these are still ominous words. As witness (marturion; martyr) they also point us towards the ‘storms that are not so much around us, but in our hearts.[note]Ibid, p.82 (Schneider)[/note]’

Heard as they must be heard, Schneider joins the chorus of voices who cry out to us today against complacency, indifference, arrogance, and the unwillingness to face the danger posed by those who seek to be our ideological masters. Dangers that we as a multi-ethnic community can still face up to together, or continue to ignore. The danger of continued indifference, though, may lead us to a place where we are bound together under those ideologies and their yoke of slavery.

“In regimenting German thought, all radio programs emanate from the – [state own broadcaster] – the Department of propaganda. Every newspaper prints only what the State wants its people to read and any letter in the German mail is subject to censorship. For in Nazi Germany any instrument that forms thought, communicates ideas; must be used to glorify the Nazi super state and its demigod.[note]Henry R. Luc, Julien Bryan, Louis de Rochemont, March of Time: Inside Nazi Germany, 1938[/note]

Each poignantly targeted at us today, Schneider’s words and example, are yet another loud theological indictment on the lifelessness of ideological servitude.

For, “the martyrs of history were not fools, and our honored dead who gave their lives to stop the advance of the Nazis didn’t die in vain.”[note]Ronald Reagan, 1964. A Time For Choosing[/note]