Nicholas Best recounts a little known story about two Lancaster bombers. One crewed by Canadians, the other by Australians*.

Early on April 29th, 1945 the two Lancasters took off from East Anglia. They flew along a previously agreed upon ‘corridor’. The route was ‘prescribed by the occupying German forces in Holland, who being cut off from Germany due to the Allied advance’, had uncharacteristically turned to the Allies for aid. They did so, on behalf of the Dutch who were suffering through a famine triggered by the Nazis. Similar to German occupation of Belgium in World War One, the German starvation of the Dutch was a means of punishment for assisting the Allies, by way of a rail strike, which had ‘prevented German reinforcements going up against the Allied assault in Arnhem during 1944.’

Best writes that the situation was dire, Holland, ‘after months of disruption as the fighting came closer, had finally run out of food.’ The situation was so bad, that ‘many Dutch had eaten their pets, and were now living on grass, sugar beet, and tulip bulbs.’

Despite ‘not having the authority to agree to a ceasefire’ [i], level-headed German officials who had sought out the Allies, reached an accord of truce. Thus, allowing the Allies to send much needed humanitarian aid.

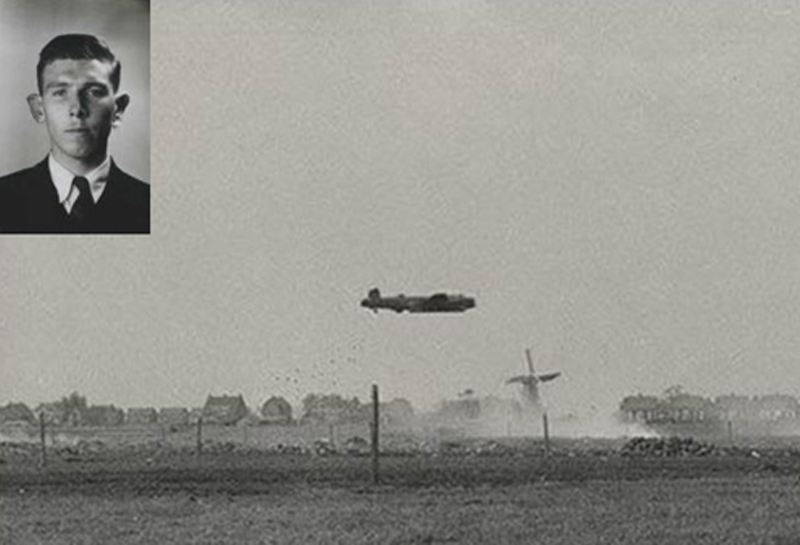

Not completely trusting of the German truce accord, the Allies flew a test mission along the agreed-upon corridor.

The test flight, as Stephen Dando-Collins wrote, ‘had all the hallmarks of a suicide mission.’ These bomber crews were ‘guinea pigs’ testing out the German agreement to not fire on the Lancaster’s flying low to deliver humanitarian aid to the starving Dutch. [ii]

The ominous mission was a success, and it kick-started Operation Manna – an unprecedented humanitarian airdrop, which involved 200 bombers, flying at low levels, dropping much-needed supplies into Nazi-occupied Holland.

The first bomber, ‘Bad Penny’, flown by Canadian, Bob Upcott led the way. He described the event in detail, testifying that:

…when we passed the Dutch coast we saw anti-aircraft guns that pointed their muzzles in our direction. We even saw tanks that tried to keep their gun barrels on us. We were looking right down a number of barrels. All the guns were still manned…The Australian pilot was on my port side [left], flying echelon port. I dropped first when we were over the race track, while the Australian dropped almost the same moment.[iii]**

The second Lancaster was flown by F/O. Peter G.L Collett, from Sydney. He was 21 at the time, and already a veteran. Along with the Canadian crew of the first Lancaster, Collett and his Australian crew* effectively spearheaded the humanitarian mission.

Collett passed away in 2012. Although his heroics are mentioned in passing chapters about Operation Manna/Chowhound, no Australian books have been written about him or his crew. Collett’s bravery isn’t taught in schools. His efforts and heroism currently only exist as a footnote.

While Upcott and his crew are celebrated, the same cannot be said for Collett. Unlike Collett, Upcott and crew remained on as an integral part of the Manna Operation, drawing a bigger spotlight on the original flight into the unknown than was given to Collett.

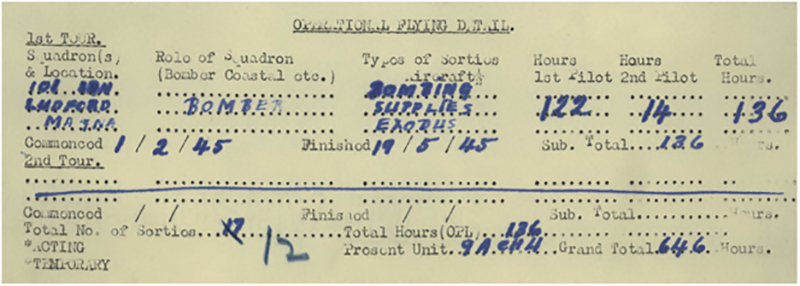

Collett’s absence from the spotlight appears to have been due to him being reassigned to Operation Exodus. Collett’s service record reflects as much. From the dates 1st February 1945, to 19th May, 1945, under 101st Squadron, right next “Bomber”, below the word “Bombing”, and above the word “Exodus”, sits the word “Supplies”, where the word Manna test flight should perhaps also be written.

Exodus ran from the 3rd April to the 31st May 1945. It involved the repatriation of liberated Allied POWs from Nazi camps in Europe. Exodus itself was an enormous undertaking, ‘1,000 people per day were brought into British receiving camps; totalling 354,000 ex-prisoners of war by the end of May.’

At 21, Collett piloted a Lancaster bomber full of humanitarian supplies, at low level, with a full crew, on a mission of mercy into occupied Nazi territory. All based on the assurance of Nazi officials who had said that the ‘mercy drop’ would be allowed to proceed without harassment from the well-armed occupying German forces.

Collett is a national hero. Yet, his heroism and the heroism of his crew isn’t mainstream knowledge in Australia. Even the Australian War Memorial’s official page for Operation Manna, called ‘Food from Heaven’, is silent about the test flight.

For an Australian/s to have played such a significant role in the relief operation, and for there to be little to no recognition of their daring and bravery, shows a real blind spot in how Australians are taught history, and how Australians embrace the importance of knowing what History teaches.

This is something to lament. This is something, we as a society, need to correct. If not for the men and women whose bold shoulders we now stand upon, at least for the generations they saved, in order to pass on the freedoms and responsibilities that allowed their own generation to stand against tyranny, in all its devouring and grotesque forms.

Lest we forget.

References:

[i] Best, N. 2012. Five Days That Shocked The World, Osprey Publishing, (pp.83-85)

[ii] Dando-Collins, S. 2015. Operation Chowdown, St. Martin’s Press (p.119)

*Confusion over Collett’s crew reinforces my point about the lack of historical interest in the Australian contribution to Operation Manna, from Australians. There are contradictory reports from various sources about whether his crew was an all Australian crew, British or mixed British and Australian.

** ‘NX579, No. 101 Sqn. Piloted by F/S Bob Upcott of Windsor, Ontario. Up at 1207, returned at 1444. 274 bags of food dropped. Second aircraft was PB350, No. 101 Sqn. Piloted by P/O Peter Collett of Sydney, Australia. Up at 1215, returned at 1442, 284 bags of food dropped.’ (RAFCommands)

You must be logged in to post a comment.