Following the news that an LGBTQ activist was suing Israel Folau for $100,000 over his “controversial” Instagram post back in April, Caldron Pool received a comment we thought worth republishing.

The comment was posted by Nicholas Butler, a “bisexual man on the left” and a law student at Monash University.

While we obviously don’t agree with everything said, Nicholas offers an interesting perspective on anti-vilification complaints that folks on the Left would do well to consider.

Nicholas’ comment was titled, ‘Why I, a bisexual man on the left, don’t support the anti-vilification complaint against Israel Folau’:

While what he said was offensive, it does not constitute aggression. So it’s wrong to respond to it with aggression, including in the law.

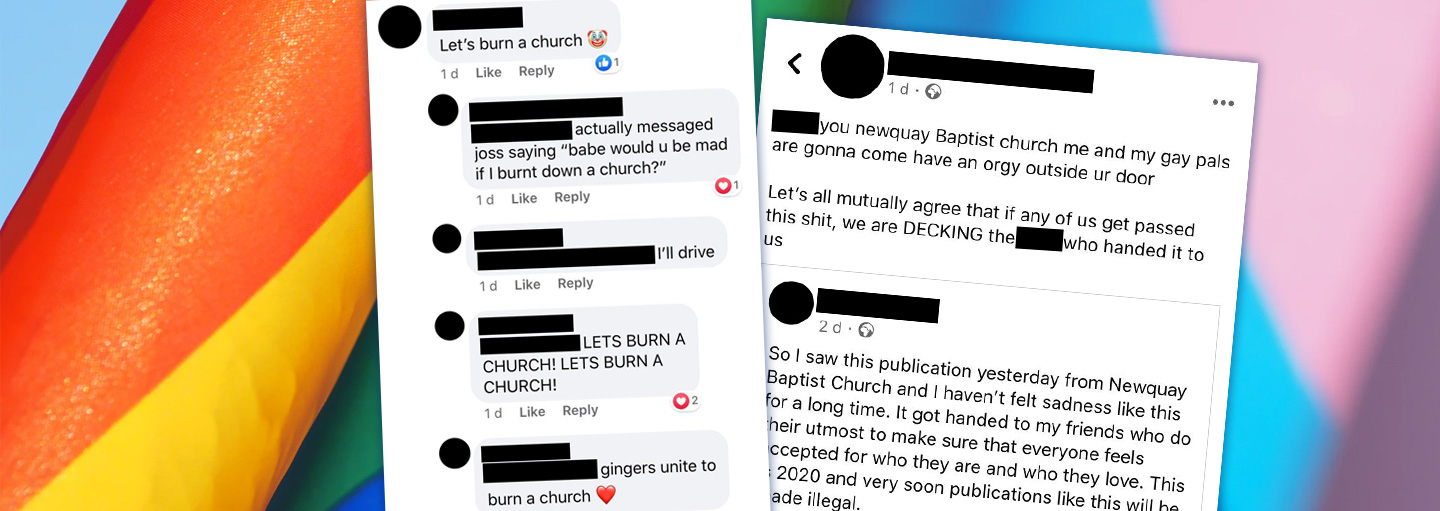

It will increase ill will towards LGBTI people, whom some will undoubtedly hold collectively responsible for the complaint, making them look like intolerant authoritarians.

It will increase the inclination towards violence among some anti-LGBTI people, who will take the following lesson away from it: speech is pointless in having your grievances addressed, and you should use other, not-so-peaceful, means.

It will give Folau a soapbox to continue to promote his views during any hearings that take place, which increases the spread of his message, rather than decreasing it.

It will cause more people to be more hurt by his comments than otherwise were, as the media reports of his comments remind those people of them over and over again.

It will prompt some anti-LGBTI commentators to move their commentary from public to private for fear of being sued, but it won’t stop them speaking completely. The result of this will be that they will speak without encountering the moderating effect of criticism and reply. Instead they will only speak among like-minded people, which will cause their beliefs to get more hardline and extreme through the phenomenon of group polarisation. I’d rather he doesn’t say it at all, of course, but it he’s going to, it’s better that he says it publicly, not privately.

It will encourage religious conservatives to think that aggressive anti-LGBTI measures are in fact justified defensive measures that will protect them from complaints like this. Many religious conservatives continue to argue that same-sex marriage should be re-illegalised because it is a threat to religious freedom. This will make that mentality even bolder. One group even suggested that the decriminalisation of homosexuality itself is a threat to religious freedom.

It will embolden conservative demands for censorship in the name of equal rights for religious people. Many conservative commentators have demanded that religious freedom laws include a prohibition on religious vilification, which would be a de facto blasphemy law. The reasoning goes “if other people are protected from offensive speech about their sexuality, we should be protected from offensive speech about our religion.”

It will encourage, to the detriment of their mental health, members of minority groups to think that if they hear something offensive, the right action to take is legal action. This implies that what he said was a very serious matter, because only very serious matters go before courts. This is detrimental to the mental health of those minorities because if you take the view that “I cannot rest until a court declares this speech illegal”, of course you will be unhappy, because you’ve made your happiness dependent on other people. But if you take the view “what he said was offensive, but I don’t care about it and don’t need to care about it,” you’ll be a lot happier. This complaint discouraged the taking of that view.

It requires that the power to censor speech be given to the state. If such power is given to the state, there is every possibility that it will be wielded in a way that you don’t like. For example, the Tasmanian government is considering a bill that would make it illegal to refer to some natural landmarks by a name other than an official designated name if it could lead a person to think that that was its official name, a clear attempt to crack down on Aboriginal names. Once the state has that power, the only way to make sure that doesn’t happen is to make sure that it only ever falls into the hands of people who think like you do, which is impossible. Or we could just take the power away from the state to begin with.

Hate speech, of course, is not harmless. But the fact that something carries certain harms does not mean government prohibition is a good solution. Government prohibition is its own policy as well, with its own set of attendant harms and benefits, and there’s no reason to assume it will necessarily make a problem better. If, as some hate speech law proponents claim, the world is so dangerously vulnerable to something like hate speech that government prohibition is necessary, how can it simultaneously be so utopianly perfect that hate speech laws will have exactly their desired effect? The resentment of being censored that is intrinsic to human nature will guarantee unintended negative consequences. I want to reduce harm, but I want to reduce all harm, not just the harm caused by hate speech. I believe that these laws and complaints result in more overall harm, not less.

Nicholas Butler is a law student at Monash University and a commentator on freedom of speech and religion.