What is the relationship between Christians and the Law of Moses? It is a question that dates back to the formation of the early church (Acts 15:24-29), but to this day, many believers still aren’t sure what they’re supposed to do with the first five books of the Bible. Often, they’re entirely avoided. Sometimes they’re treated like off milk that passed its expiration date with the coming of Jesus. Other times, they’re presented as cruel, harsh, and unforgiving rules, reflective of the barbaric and uncivilised era from which they emerged.

Whatever the case may be, portraying the Law as anything short of “holy, righteous, just, and good” is to present the Law in a way that is contrary to the New Testament (Rom. 7:12). Jesus, the Apostle Paul, and James all summed up the Law in a word: Love (Mk. 12:31; Rom. 13:9; Jam. 2:8; cf. Lev. 19:18). In other words, in the New Testament, “love” was not some arbitrary sense of affirmation or positive vibes. Love was a summary of God’s Law.

To love God “with all your heart, soul, and strength,” was to love him in accordance with the commandments he had given (Deut. 6:4-5; 10:12-13). To love your neighbour as yourself, was to treat your neighbour the way in which God prescribed in his statutes, and to do so from the heart (Lev. 19:18-19). To relax even one of the least of the commandments was to love God and man less than God required (Matt. 5:19). It was to act presumptuously by elevating yourself to the level of the Law Giver. In fact, the preservation of love was so important in Israel that violations were regarded as a crime punishable by death (Deut. 17:12-13).

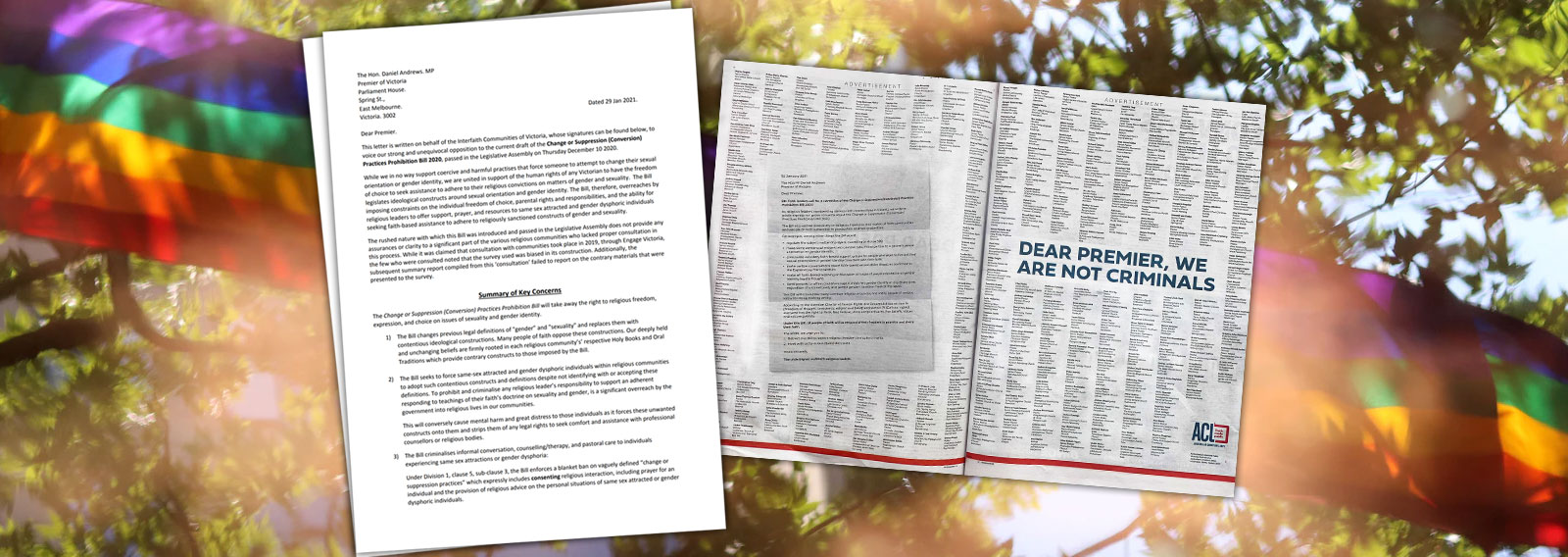

It is at this point that many modern Christians recoil. The Law required capital punishment for sins that our culture does not. And sometimes, it demanded death for sins that our culture celebrates. To affirm the Law as “love” is perhaps the most counter-cultural thing you can do. It could cost you your family and friends, your career, and in some instances, your freedom. Wouldn’t it be easier, for the self-preserving Christian, to pretend God’s Law was no longer relevant? To opt rather for a definition of “love” that’s defined more so by current social sentiments than by Scripture? After all, didn’t Jesus dismiss the harsh demands of the Law for the higher road of compassion and forgiveness? That is what we’re told.

It’s rare that the subject of God’s Law and it’s relevance today is discussed without someone making an appeal to John 8:3-11. The incident of the woman caught in adultery is often raised as evidence that Jesus disobeyed the Law demanding death to establish a new “Law of Love” that operates, at times, contrary to the Law. Arguments regarding the account’s placement in Scripture aside — let’s just assume it belongs here — a question worth considering is whether the incident demonstrates an example of Jesus, at best, lowering the standard of the Law, and at worst, directly violating it.

It’s an important question to consider, as our understanding of this will determine whether we believe Jesus transgressed God’s Law, thereby sinning, and consequently rendering himself an unfit sacrificial substitute for our sins (1 Jn. 3:4; Heb. 9:14). Of course, this would be at odds with the witness of the New Testament which tells us that Jesus, who was born under the Law (Gal. 4:4-5), never transgressed the Law, nor could he be found guilty of any sin (Jn. 8:46). This is a claim that the Apostles also reaffirm in the epistles (2 Cor. 5:21; Heb. 4:15; 1 Peter 2:22; 1 Jn. 3:5). So, if Jesus did not sin, then he did not transgress the Law. How then do we make sense of his interaction with the woman caught in adultery?

The fact that Jesus never sinned by transgressing the Law is highlighted by the scribes and the Pharisees who were “searching for a charge that they could bring against him.” In John 8:6, we’re told that Jesus’ opponents wanted to put him to the test. So, they brought before him a woman who had been caught in the act of adultery. The scribes and Pharisees then said to Jesus, according to the Law, “Moses commanded us to stone such women. So, what do you say?” The scribes and Pharisees were appealing to Leviticus 20:10, which states: “If a man commits adultery with the wife of his neighbor, both the adulterer and the adulteress shall surely be put to death.”

The scribes and Pharisees were setting a trap for Jesus. Under Roman rule, the Jews were not at liberty to put anyone to death (Jn. 18:31; Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 1.1; 7.2; Palestinian Talmud, Sanhedrin 41a). If Jesus upheld the Law of Moses, he would be violating the law of Rome. If he upheld the law of Rome, he would be violating the Law of Moses. Whatever his answer may be, he would either be guilty of a sin against God or a crime against Rome. Either way, the scribes and Pharisees would have their charge to bring against him.

They were clever, but they were no match for Jesus. At their challenge, we’re told that Jesus stood up and responded to his opponents saying, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” When the scribes and Pharisees heard this, John tells us they all walked away, one by one, until only Jesus and the woman were left. Jesus said to her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, Lord.” So, Jesus said to her, “Neither do I condemn you; go and from now on sin no more.”

It’s at this point that it’s often assumed Jesus effectively lowered the “harsh” and “unforgiving” standard of the Law to get himself and the adulteress woman off the hook. In many modern minds, Jesus dismissed Moses, upheld Roman Law, and justified his answer by adding an unattainable criterion to God’s Law that only the sinless should obey it. But are we supposed to think that the scribes and the Pharisees who had a murderous hatred for Jesus (Jn. 5:18) and wanted to bring a charge against him were suddenly fine with simply disregarding the Law because, after all, we all violate it in some way or another?

Sinlessness was not a prerequisite for obedience, and Jesus’ opponents knew it. In fact, the sacrificial system built into the Law presupposed that its adherents were not without sin. There is obviously more to this story than we’re usually told. How often have you heard it said that Jesus set aside the Law in this instance to establish “forgiveness” and “grace” in its place?

In retellings of this account, the scribes and Pharisees are often presented as villains for their strict obedience to the demands of the Law. In contrast, Jesus is portrayed as kind and compassionate, willing to dismiss the Law’s severe demands and lower God’s high standards in favour of a more “loving” approach. But if this were the case, as we’ve already noted, Jesus himself would be guilty of transgressing the Law he was supposed to fulfil. Yet, we know Jesus didn’t transgress the law, as just a few verses later, he admits that his opponents were unable to convict him of any sin (Jn. 8:46). So, what is going on here?

Our problem is that we have the story entirely backwards. It is not the scribes and the Pharisees who are the strict adherents to the Law, but Jesus. It is not Jesus who is lowering the strict standard of the Law, but the scribes and Pharisees. It is not the scribes and the Pharisees who are preserving and upholding the Law, but Jesus. It is not Jesus who is deviating from the Law to establish a new standard, it is the scribes and the Pharisees. But how was this the case if Jesus pardons the woman when the Law required her death?

Jesus’ opponents did not up and leave because they suddenly realized that only the sinless could hurl the first stone. That was never a requirement for obedience under the Law. The scribes and Pharisees left because Jesus highlighted the fact that they had sinned by failing to meet the requirements of the very Law to which they were appealing (i.e. Lev. 20:10). Moses did not just command Israel to “stone such a woman,” as Jesus’ opponents claimed. He also demanded that no one be put to death without sufficient evidence. This included the testimony of at least two eyewitnesses.

As Deuteronomy 17:5-6 states: “…you shall stone that man or woman to death with stones. On the evidence of two witnesses or three witnesses, the one who is to die shall be put to death; a person shall not be put to death on the evidence of one witness.”

When the scribes and Pharisees brought the woman before Jesus and accused her of committing adultery, there were no eyewitnesses to act, evident by Jesus’ response: “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” This was not Jesus’ effort to dismiss or lower the standard of the Law, but to maintain it. The very next verse in Deuteronomy 17 stipulates that the first stone to be hurled is to come from the hand of those who testified as witnesses to the act.

Verse 7 states: “The hand of the witnesses shall be first against him to put him to death, and afterwards the hand of all the people. So you shall purge the evil from your midst.”

The absence of the first stone meant the absence of sufficient witnesses. The absence of witnesses meant the scribes and the Pharisees were guilty of violating the requirements of the Law. The first stone, if it were to be thrown, could therefore only be hurled in sinful defiance of Deuteronomy 17:7. If there were no witnesses, then a false witness was necessary. And Jesus’ opponents knew well that to be exposed as a false witness is to sentence yourself to the same fate as your victim (Deut. 19:18-20). No one was prepared for that, and so we see the scribes and Pharisees departed, “one by one, beginning with the older ones.”

Jesus was not setting aside the Law of Moses (Heb. 10:28), but the opposite. He was upholding it. This incident is not a lesson in dismissing God’s Law, but in preserving it. It was in Jesus’ obedience to the Law that the guilty woman escaped death. Jesus knew that she had sinned. That is why he charged her to “sin no more.” What her accusers lacked was the lawful grounds for warranting the execution in keeping with the Law of God.

What we find in this account is that it was the scribes and Pharisees, the villains of the story, who were guilty, once again, of setting aside the commandments of God (Matt. 15:6; Mk. 7:8-9). It was Jesus’ opponents who lowered God’s righteous standard, who relaxed the Law, and whose definition of “love” was not within the bounds of the Law.

Jesus, on the other hand, upheld the Law. He demanded that its requirements be fully met. It was the lowering of the Law’s standard that demanded the adulterous woman’s immediate execution. It was the strict adherence to the Law’s standard that preserved her life. John 8 is not a lesson for us in pious disobedience to God’s Law. We cannot set aside what God has decreed under the guise of “love” or “justice” because it is God alone who defines what these things look like.

So, the next time you hear somebody appealing to Jesus’ supposed selective obedience in John 8 as an indication of how we are to relate to the Law, remind them that they’re really siding, not with Jesus, but with the villains of the story.