Different writers have pointed out that the Bible was written from the perspective of the oppressed. There is some truth in this, obviously. While Joshua was written from the perspective of the conqueror, Moses was the son of slaves in Egypt, and he wrote the first five books of the Bible. The exiles again were a conquered people. But there is something that those who oversimplify this view forget to account for.

They will often use the Bible to say we need to be critical of white privilege, male privilege, etc. But the Bible is not interested in criticizing these things, ever. Indeed, it is often as critical of the conquered as the conqueror.

Think about this, the Jews in Jesus’ and Paul’s day were the conquered. Judea was naught but a dominated province of Rome. But the New Testament does not spend any time criticizing the “conqueror” coming into the church, but it has entire books that heavily criticize the “oppressed” seeking to change the “conqueror” worshipping amongst them.

Conquered peoples often have a strong aversion to those who rule them. This was true of the Jews. This can make them very cliquey, which was again true of the Jews. Conquered peoples often have a strong pride in having endured oppression, this was also true of the Jews. “Jewish pride” would be a way to summarize the Pharisee movement, the Zealot movement and other aspects of the Jewish culture in that era.

Yet Paul never told the Gentiles coming into the church they had to repent of their benefitting from Rome’s power, nor did he tell them that they had to dismantle their male or ethnic privileges of having been part of the Roman patriarchal empire. He never said any of this.

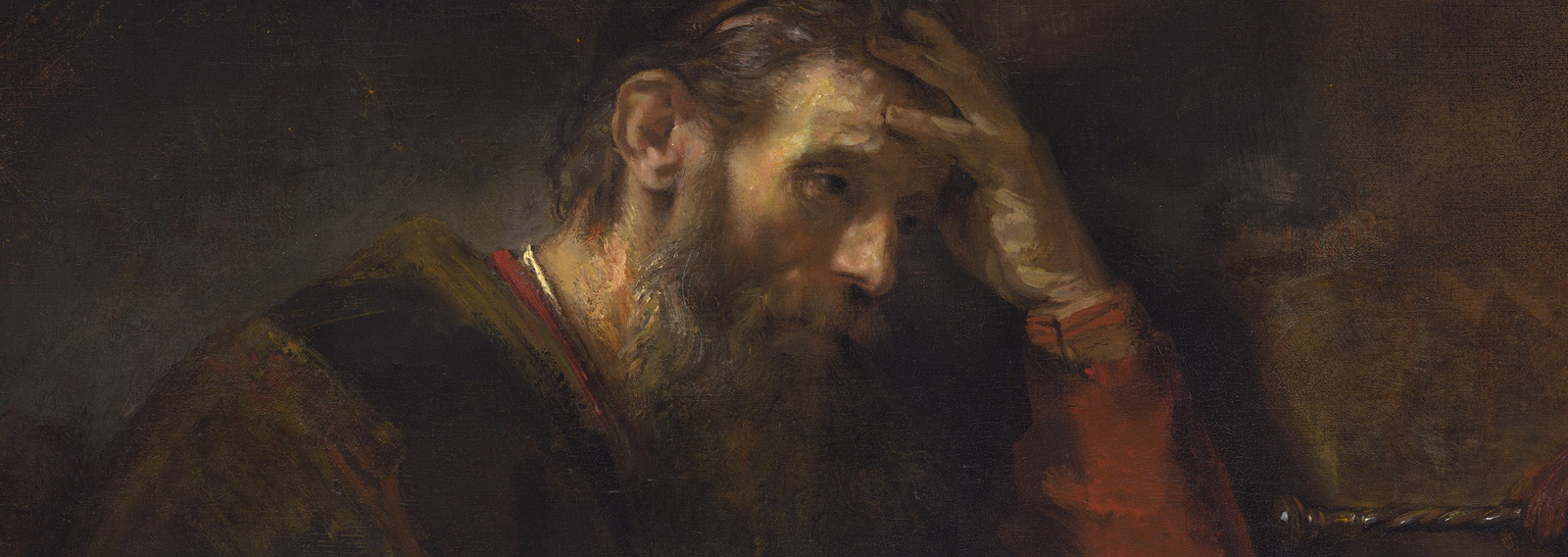

If the Bible was a critical theory handbook there would be less criticism of the Jews, and more criticism of the Greco-Roman peoples coming into the church. Paul would have told them to give up their privilege of being Romans, but he never did, indeed he often took advantage of such privileges when necessary in his own ministry journals. The Bible is not a critical theory handbook, neither did Paul teach this in his writings.

Instead, he criticized the Jews in the churches for being too exclusive with these new people, even though the Jews were the oppressed, and the Greco-Romans the conquerors. Paul’s criticisms of Jewish pride, and expecting newly converted Gentiles to become like the Jews, is directly relevant to criticizing black pride movements which expect white people to acknowledge their struggle and change to suit the “oppressed”.

Paul, to the chagrin of the critical theorists, avoided such nonsense, and rather told the “oppressed” peoples, his fellow Jews, to stop thinking they were better than these newly converted “oppressor” peoples by virtue of their ethnic identity. The only identity which matters in the Church is that which is found in Christ.

The whole critical theory outlook falls down like a shaken house of cards in the face of Paul dedicating a lot of his work to criticising the “oppressed” as much as, if not more than the “oppressors”. Paul was interested in critiquing sinners, which no nation is exempt from being filled with.

Christians today excusing black pride movements in the church because of historical oppression would be directly the same as Christians of Paul’s day excusing Jewish pride movements, because Rome had conquered them. But Paul didn’t do it.

In the Bible, being an oppressed minority, is no excuse for bringing up such things in the church. Paul’s argument was simple: eat with those who you consider your historic enemy, because in Christ ethnicity is no obstacle to salvation. There is only one body of Christ and all can be a part of it by virtue of faith in Jesus.

Faith in Jesus, and obedience to his teachings, is what matters for salvation and Church, more than anything else.