The Aussie Care Network recently reported that “An Australian researcher Dr Helen Adam, has warned that classic and popular children’s stories such as The Very Hungry Caterpillar and Harry The Dirty Dog could be harmful to children as they fail to portray diverse characters.”

Citing childhood classics such as The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Hairy Maclary, Wombat Stew, We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, and Where the Wild Things Are, Dr Helen Adam believes that they all not only represented, “outdated viewpoints and lifestyles”, but also said that:

‘Purely and simply this research shows, there’s a lack of representation of boys and girls in non-traditional gender roles in these books – this can contribute to children from these families and backgrounds feeling excluded or marginalised.’

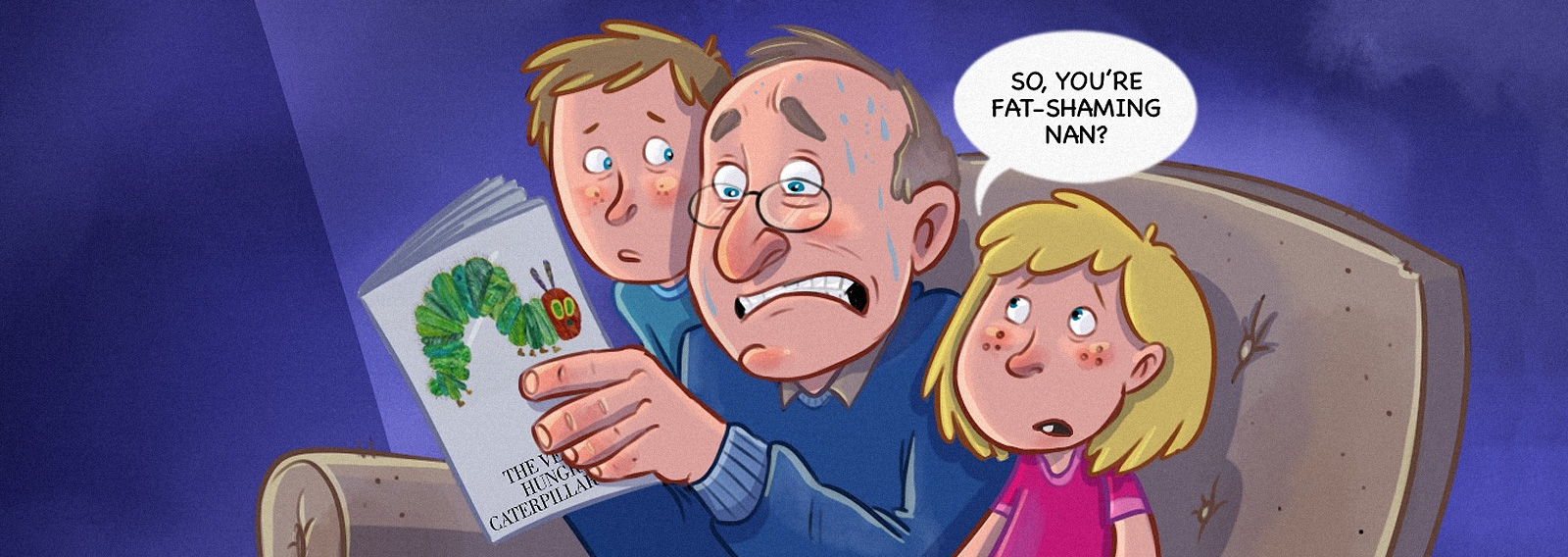

Someone might ask, ‘How does The Very Hungry Caterpillar transgress the latest progressive norms?’ Is it somehow fat-shaming people who eat too much? Apparently not. I actually think there’s a missed opportunity here since—rather than cancelling the book—leftist academics such as Adams, could have reappropriated the work to support transgenderism. Especially since the story is about a caterpillar turning into a beautiful butterfly.

The article then goes on to quote Rachel Adamson, the co-director of Zero Tolerance, a charity working to end men’s violence against women. Similarly, to Dr. Helen Adam, Rachel Adamson believes that the children’s book, The Tiger Who Came to Tea, has the potential to harm children by promoting domestic violence and sexual abuse through the framework of traditional gender roles. As Adamson states:

‘We know that gender stereotypes are harmful and they reinforce gender inequality, and that gender inequality is the cause of violence against women and girls, such as domestic abuse, rape and sexual harassment.’

Significantly, The Tiger Who Came to Tea was written by a woman, Judith Kerr. First published in 1968, the book has become so popular that it has never been out of print. If you never had young children, or have somehow escaped the delightful duty of bedtime story hour the last fifty years, below is a dramatic reading:

For everyone else, the story is about a mother and daughter’s home and dinner being turned upside down by a renegade tiger. (Although, towards the end of the book it becomes obvious that it might have just been the family orange-and-black, tabby cat) When the father comes home from work though, there’s no supper and the house is a mess.

But what does he do? Fly into a patriarchal rage and rail against the two defenceless women? No, he instead calmly takes them all out for a lovely British supper, complete with sausages, chips and ice cream. So much for promoting some form of hypertoxic masculinity.

But of even greater importance is the underlying thesis of this progressive trope that traditional gender roles promote intimate partner violence (IVP). The academic article, “Same-sex intimate partner violence: Exploring the parameters”, in the book edited by B. Scherer, Queering Paradigms (New York: Peter Lang) explores why IVP is greater amongst same-sex couples than heterosexual ones.

What’s more, according to the Australian Government’s own website, over 40% of homosexual men and almost 30% of lesbians have experienced DV within a same-sex intimate partner relationship. What’s more, according to the LGBTIQ community, this “is twice the rate for men and almost three times that for women, respectively, with a history of only opposite-sex cohabitation.”

Why is this the case? Well, the nature of DV within the LGBTIQ community involves complex notions of power. Not only that, but DV between same-sex couples is, more often than not, mutual rather than being perpetrated by just one of the partners. What’s more, the outworking of the abuse may have nothing to do with physical violence at all—although tragically, in LGBTIQ relationships that does still also occur—but instead involves emotional, financial, and especially sexual control. As the Australian Government’s own website concludes:

‘Concepts such as ‘intimate terrorism’ and ‘coercive control’ are thought to be useful for defining intimate partner violence in LGBTIQ populations as these definitions emphasise that intimate partner violence is primarily defined by patterns of coercion, power and control.’

All of which is to say, traditional gender roles are not the problem. It’s what the Bible identifies as sin. A human heart that has been morally corrupted due to our shared spiritual rebellion. And as such, maybe returning to more wholesome conservative role models, as illustrated in children’s books of the past, might actually help, rather than hinder, what it means to be a healthy husband and father.

This is because God designed for children to have a father and mother, rather than two people of the same gender. That model has worked for every civilisation—regardless of its religion—over thousands of years. And the increased level of intimate partner violence amongst same-sex relationships proves that this is so.