Welcome to 2020, when looting has its own literature.

At the start of the year, few could have predicted widespread riots and looting in the great cities of America — even with a heated election on the horizon. But the world watched in shock as tensions boiled over in the wake of George Floyd’s killing and cities burned.

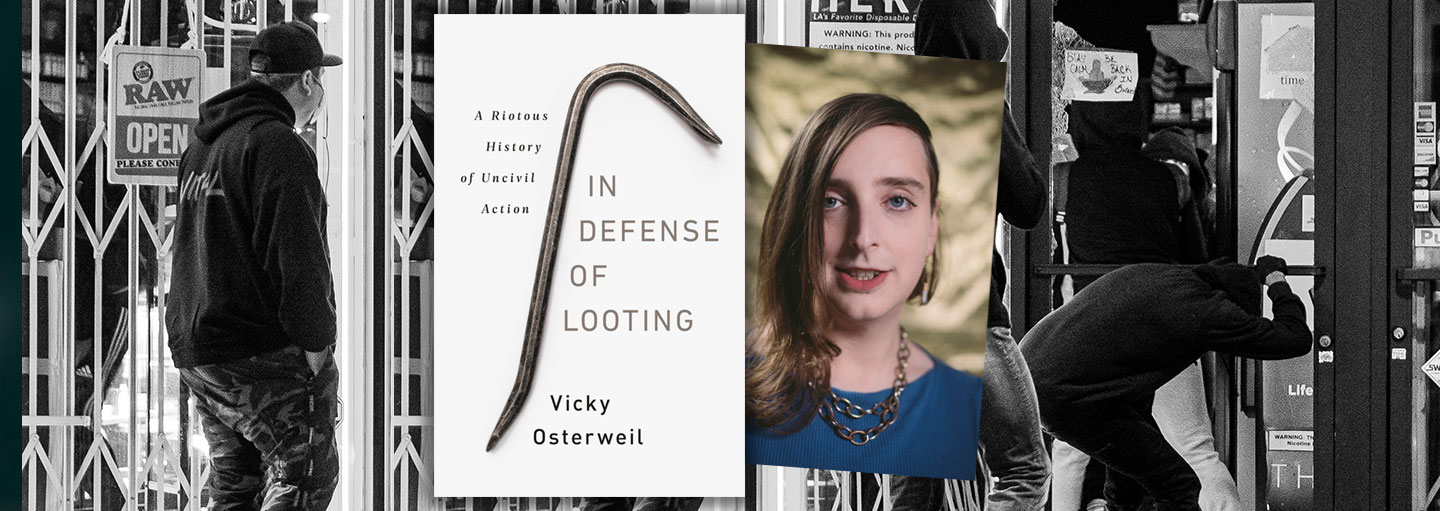

If we couldn’t predict this, much less could we have seen that looting would end up with its own literature. But welcome to 2020. Vicky Osterweil’s In Defence of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action is the latest book to catch the world’s attention — all thanks to National Public Radio (NPR), a taxpayer-funded media group, no less.

Osterweil, a transwoman who describes herself as a writer, editor and agitator, has been fascinated by and involved in protests for many years. In her new book, she argues that “looting is a powerful tool to bring about real, lasting change in society”.

While it would be easy to dismiss her case out of hand, perhaps it warrants deeper reflection. As early as the 300s, for example, Church Father Saint Basil of Caesarea taught in a sermon that the poor actually have a rightful claim to the wealth of the rich:

“That bread which you keep belongs to the hungry; that coat which you preserve in your wardrobe, to the naked; those shoes which are rotting in your possession, to the shoeless; that gold which you have hidden in the ground, to the needy.”

Likewise Godfrey of Fontaines (1250-1309), a medieval theologian, claimed that if a beggar stole a loaf of bread from his rich neighbour, he couldn’t be charged for theft since he had a natural right to that bread in order to survive.

In fact, Congresswoman AOC, who loosely defines herself as a Catholic, seemed to echo this logic when she defended the looting in New York City:

“Maybe this has to do with the fact that people aren’t paying their rent and are scared to pay their rent and so they go out and they need to feed their child and they don’t have money so… they feel like they either need to shoplift some bread or go hungry.”

A Black Lives Matter organiser from Chicago also made this justification when she announced to gathered crowds: “I don’t care if somebody decides to loot a Gucci’s or a Macy’s or a Nike because that makes sure that that person eats… that’s reparations. Anything they want to take, take it because these businesses have insurance.”

Is this what Saint Basil or Godfrey meant? Is looting ever morally justifiable? Moreover, what exactly does Vicky Osterweil have in mind in her defence of looting?

“When I use the word looting,” explains Osterweil in the NPR interview, “I mean the mass expropriation of property, mass shoplifting during a moment of upheaval or riot. That’s the thing I’m defending.”

She goes on:

“Often, looting is more common among movements that are coming from below. It tends to be an attack on a business, a commercial space, maybe a government building — taking those things that would otherwise be commodified and controlled and sharing them for free.”

Referring to looting as “proletarian shopping”, Osterweil makes the case that looting “rejects the legitimacy of ownership rights and property, the moral injunction to work for a living, and the ‘justice’ of law and order”. More than this, says Osterweil: “Looting provides people with an imaginative sense of freedom and pleasure and helps them imagine a world that could be… riots and looting are experienced as sort of joyous and liberatory.”

But what of the damage they cause? Says Osterweil: “In terms of potential crimes that people can commit against the State, it’s basically nonviolent. You’re mass shoplifting. Most stores are insured; it’s just hurting insurance companies on some level. It’s just money. It’s just property. It’s not actually hurting any people.”

Unfortunately, that hasn’t been true for the countless shop owners in recent months who have lost livelihoods — and even their own lives, in a fight to defend their property. In one tragic case, a torched corpse was found in a Minneapolis pawnshop days after rioters had passed through.

Ironically, many of those who have suffered the worst losses are themselves from minority communities.

And the broader community suffers too. Insurance rates go up, and during the long recovery, local jobs are harder to come by, and groceries and medicines are harder to access.

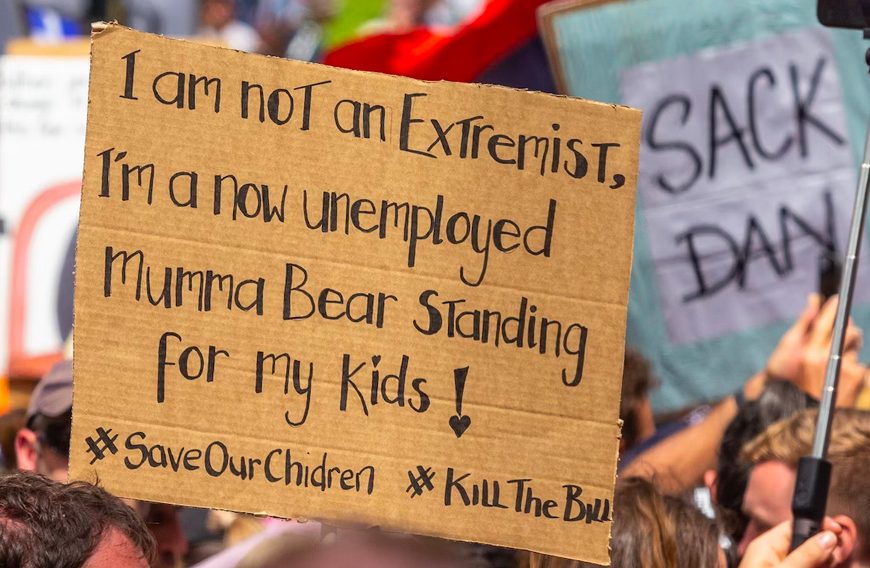

This is why the mother of Jacob Blake, the African-American shot by police in Kenosha, told the media: “If Jacob knew what was going on as far as that goes, the violence and destruction, he would be very unpleased. Please don’t burn up property and cause havoc and tear your own homes down in my son’s name. You shouldn’t do it.”

To Osterweil, looting is fun — for the looters. It’s free — also for the looters. And it doesn’t hurt anyone — at least, not the looters.

But the high costs of it all are borne by everyone else.

In Osterweil’s utopian thinking, scarcity simply doesn’t exist. And property rights don’t either, since there will always be enough to go around.

This is the eternal flaw in Marxist logic. Redistribution — by law or by looting — may work in the short-term. But it kills the will to produce in the first place.

Basil, Godfrey and even I would happily forgive a beggar stealing something they really needed. But no one wants their livelihood stolen or their community trashed. And that is precisely what looting leads to.

As a reviewer of the book at The Atlantic asked: “What do you think will do more for your community — a store that employs six people, or in that same location, a pile of bricks and broken glass?”

In truth, Osterweil’s book undermines her own argument. Like every book on the market, its publishing declares that “the scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property”.

Apparently looting is only fun, free and harmless when you’re the one doing it.