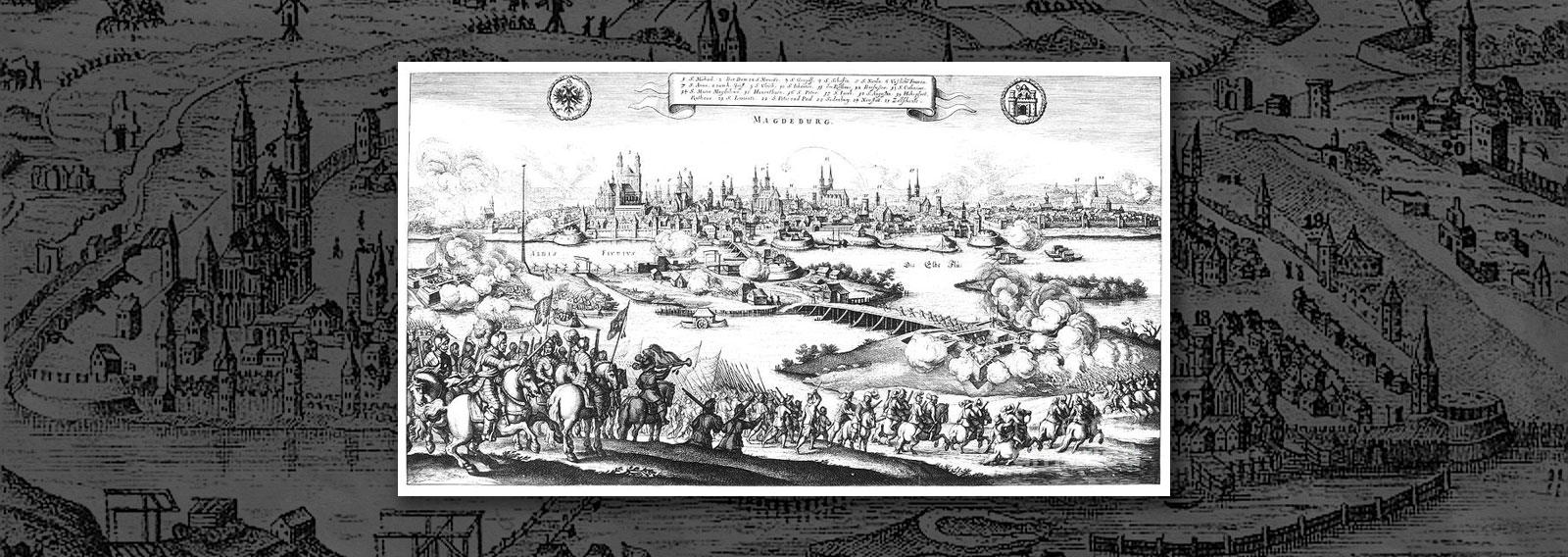

One of the earliest Protestant statements on the place of resistance to wicked rulers is the Magdeburg Confession. The confession was written by a group of German pastors at Magdeburg laying out why they had to resist the 1548 Interim of Charles V. Among other things, it set out the doctrine of the lesser magistrates, but more on that in a moment.

Given that religion and politics were so closely intertwined at the time, it is not surprising that the Confession dealt with both matters. But before proceeding, a bit of an historical overview – via a timeline – should be offered here.

Timeline

- 1483 – Luther is born.

- 1497-1498 – Luther a student at Magdeburg.

- 1505 – Luther’s conversion.

- 1517 – Luther posts his 95 Theses.

- 1521 – The Edict of Worms condemns Luther and the Reformation.

- 1530 – The Diet of Augsburg convened by Charles V to deal with religious differences. Philip Melanchthon represents Luther, with the “Augsburg Confession” being presented there.

- 1531 – The Schmalkaldic League is formed. It was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire. The Lutheran city Magdeburg is one of the first to join.

- 1546 – Luther dies.

- May 15, 1548 – Emperor Charles V imposes his Interim, seeking to force Protestants back into Catholicism.

- April 13, 1550 – The Magdeburg Confession is written.

- October, 1550 – The siege of Magdeburg begins.

- November 4, 1551 – The siege is lifted after the defenders of the city withstand the forces of Charles V.

The Confession is short (around 90 pages in English text) and has three main parts. It restates various principles and beliefs enunciated by Luther, and in the ‘Second Part’ it famously discusses the role of the lesser magistrate to stand up against ungodly tyrants. In the Colvin translation (see reading list below) it goes from pages 47-72.

It should be pointed out that the word “magistrate” here means any form of civil government or civil ruler, be it a king or prince or governor or president. This section is comprised of three arguments. The first argument opens with these words:

The Magistrate is an ordinance of God for honor to good works, and a terror to evil works (Rom. 13). Therefore when he begins to be a terror to good works and honor to evil, there is no longer in him, because he does thus, the ordinance of God, but the ordinance of the devil. And he who resists such works, does not resist the ordinance of God, but the ordinance of the devil. But he who resists, it is necessary that he resist in his own station, as a matter of his calling….

When, moreover, he deposes an inferior [lesser] magistrate who is unwilling to obey him in such a crime, and replaces him with someone who is willing, by the very fact that he now honors and promotes evil works, and dishonors and destroys the good, he is no longer the ordinance of God, but the ordinance of the devil…

The writers go on to distinguish between various levels of wrongdoing or evil: “Here we must also distinguish different degrees of offense or injury. Since there is a great difference between them, we must consider whom a magistrate is able and ought to resist, and in what way, lest we suppose that we are permitted to make any injury we choose into an opportunity to disturb our superiors.”

They examine four such levels or degrees and say of course that only the most severe of them warrant such resistance. Thus they say of the final level:

The fourth and highest level of injury by superiors is more than tyrannical. It is when tyrants begin to be so mad that they persecute with guile and arms, not so much the just persons of inferior magistrates and their subjects, as their right itself, especially the right of anyone of the highest and most necessary rank; and that they persecute God, the author of right in persons, not by any sudden and momentary fury, but with a deliberate and persistent attempt to destroy good works for all posterity.

The second argument begins as follows:

When Christ commands, with an affirmative and by clear inference, that the things which are Caesar’s are to be rendered unto Caesar, and the things which are God’s to be rendered unto God, we rightly infer from the affirmative a negative, likewise by clear inference, just as negative commandments, as in the Decalogue, always include an affirmative sentence by direct inference. And so by the force of this precept, the things which are God’s are not to be rendered unto Caesar, just as the Apostles hand down this rule and precept, “We must obey God rather than men.” And by refusing obedience to superiors in those things which are contrary to God, they do not violate the majesty of their superiors, nor can they be judged obstinate or rebellious, as Daniel says, “I have committed no crime against you, O king.”

The third and final argument begins this way:

If God wanted superior magistrates who have become tyrants to be inviolable because of his ordinance and commandment, how many impious and absurd things would follow from this? Chiefly it would follow that God, by his own ordinance and command, is strengthening, nay, honoring and abetting evil works, and is hindering, nay, destroying good works; that there are contraries in the nature of God Himself, and in this ordinance by which He has instituted the magistrate; that God is no less against his own ordinance than he is for the human race.

And it continues:

God has always punished wicked men, and especially tyrants, partly without the ministry of men, by His own various means, some secret, others open; and partly through the instrumentality of men. Again, sometimes He punishes the wicked themselves by means of the wicked; but ordinarily He does so through those who are called to exercise just punishment, according to what is said about homicides: “Whoso sheds man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed” (Gen. 9). This means of carrying out punishment and driving off unjust violence is divine and belongs to magistrates, whether to the superior against the inferior, or to an equal against an equal, or to an inferior against a superior.

The entire document is worth reading. Of course, like all human creeds, confessions and documents, it is not a perfect one, free of error, nor is it divinely inspired. And how exactly any applications of this might be made today raises plenty of questions. And bear in mind as well that this document is not saying anyone can resist tyrants, but only magistrates of different standings – be they superior, inferior or equal.

But its importance has stood the test of time. It especially came to the fore just a few years ago when the Covid reign of terror descended upon much of the world. It was then that many Christians finally woke up to the need to revisit biblical texts like Romans 13:1-7 and learn to draw a line in the sand against unjust tyrants and ungodly tyranny. As this globalist statism is likely to only get worse in the days ahead, returning to these older documents becomes more needful than ever.

In closing, let me quote some of what George Grant has to say in his introduction to Colvin’s translation of the Confession:

[T]hroughout the entire fifteenth century, cries for the reformation of both church and society came from every sector. From traditionalists to innovators, from mendicants to oblates, from magistrates to hierarchs, and from those who had vested interests to those entirely on the outside of the system, nearly everyone agreed that substantial reforms needed to take place. It was evident to even the most disinterested observer that the West would have to be dramatically revitalized if it were to survive, much less to thrive.

Virtually no one disagreed on the fact that the West needed to be reformed. What they disagreed on was what that reform should entail and how it was to be effected. In frustrated tension, dozens of competing factions, sects, schisms, rifts, rebellions, and divisions roiled just beneath the surface of the West’s tenuous tranquility for decades. Finally, on October 31, 1517, those pent-up passions burst out into the open when an Augustinian monk named Martin Luther posted his “Ninety-Five Theses” on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. In a single stroke, not one, but two momentous renewal movements were launched that at last were able to effect genuine reform within the church: the Protestant Reformation and the reaffirmation of covenantal principles to civil governance.

This is the essential historical and cultural framework out of which the Magdeburg Confession of 1550 was written. Against the backdrop of the centralizing totalitarianism of the Hapsburg hegemony, the newly revived Holy Roman Empire, the people of the little German town of Magdeburg, situated between Berlin and Hanover, not far from Brandenburg, determined to recover their federal, their covenantal, their Biblical culture.

Their confession of faith asserted that Biblical covenantalism was the principle by which men and nations might know the truth of the Gospel and thus afford hope for their souls, it was simultaneously the principle by which their cultural and political and social freedom might be won.

Ultimately, the font of covenantal ideas in the Magdeburg Confession flowed out into the reforming nations of the West: they were echoed in Calvin’s Geneva; they helped shape Knox’s Scotland, they were influential in Bucer’s Strassburg; they laid the foundations of Cranmer’s England; and as we have seen, they were central to the vision of the Founders of America’s great experiment in liberty.

But for the same reasons that the Magdeburg pioneers had to recover the old Medieval principles of covenantal federalism by means of reformation, we need to pay heed to these ideas today. Western Civilization is once again in very real jeopardy. Freedom is once again threatened. Life, liberty, and opportunity are once again coming under the shadow of vested centralized powers and principalities.

We should all be grateful that this new translation, this new edition of the Magdeburg Confession is now available. By looking back at the essential notions upon which our freedoms were built we may yet be motivated and equipped to begin the process of reforming, restoring, and recovering. May it be so, Lord.

References and further reading

Colvin, Matthew, translator, The Magdeburg Confession. 2012.

Mortimer, Sarah, Reformation, Resistance, and Reason of State (1517-1625). OUP, 2021.

Sunshine, Glenn, Slaying Leviathan. Canon Press, 2020.

Trewhella, Matthew, The Doctrine of the Lesser Magistrates. CreateSpace, 2013.

Whitford, David, Tyranny and Resistance: The Magdeburg Confession and the Lutheran Tradition. Concordia, 2001.

Witte, John, The Reformation of Rights. CUP, 2002, 2010, esp. pp. 106-114.