Biblically literate Christians in general, and those aware of the church-state debates of the past two years in particular, will know what my title refers to. I of course have in mind the most important – certainly the most lengthy – passage in the entire New Testament about how the Christian should view civil government.

Romans 13:1-7 is not the only text to deal with this, but it is the major one that all such discussions flow from. Needless to say, I have written about this often. See especially these four pieces for more detail:

- Christians and the State

- Difficult Bible Passages: Romans 13:1-7

- The State Is Not Absolute

- Romans 13 Revisited

My thesis is simple: too often believers think that what Paul meant when he wrote those seven verses is that we must all blindly submit to the state at all times – no questions asked. They take his words as some sort of absolute and inviolate command to do whatever the state demands.

But this is not what Paul had in mind. To guide my discussion here I want to appeal to just one important book by one important thinker, the Christian philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff. The book is this: The Mighty and the Almighty: An Essay in Political Theology (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Although this volume has been out for a decade now, it is still worth revisiting. Although rather brief (180 pages), it is a tightly argued philosophical and theological discussion of Romans 13 in particular, and how believers should understand state authority – and its limits.

And that is a key theme: the authority and scope of the state is limited indeed. It is limited by God, who is the one, supreme authority. The authority that the state has is delegated authority. When the state does what God has authorised it to do, the believer should obey it. But when it does not, the believer need not obey – indeed, the believer at times may need to resist the state when this happens.

This will not be a proper book review, nor will I seek here to outline the argument that he makes throughout. Instead, I will focus mainly on his chapters where he discusses in more detail what Paul had in mind when he penned what is now known as chapter 13 of Romans.

Wolterstorff begins and ends his book by looking at the life of the early Christian martyr Polycarp. Like all believers, he held two passports. He was a citizen of heaven, but also of a locality here on earth (Smyrna). But Christ came first, and he could not swear loyalty to Caesar.

As he famously said before being burned at the stake: “For eighty and six years have I been his servant, and he has done me no wrong; how then can I blaspheme my King who saved me?” While earthly rulers have limited sovereignty, given to them by God, only the one true God has full sovereignty, and only he can demand complete loyalty and obedience of us.

Polycarp knew that earthly rulers were appointed by God, but he also knew that when they overstepped their bounds, they no longer merited our submission. So just what are those bounds? That is a key area that Wolterstorff explores. He examines various thinkers on this, ranging from Calvin to Kuyper to John Howard Yoder.

Being in the Reformed tradition, he spends most of his time on Calvin, but he argues that Calvin and others tended to get it wrong on Romans 13. That is, he and others put the primary emphasis on verse one, while he believes verses 4-5 are the key, and become the focus of how we are to understand v. 1.

Those verses are what should be “the center of interpretation” he argues. But before proceeding, let me at this point simply present these verses here:

1 Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. 2 Therefore whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. 3 For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, 4 for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer. 5 Therefore one must be in subjection, not only to avoid God’s wrath but also for the sake of conscience. 6 For because of this you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, attending to this very thing. 7 Pay to all what is owed to them: taxes to whom taxes are owed, revenue to whom revenue is owed, respect to whom respect is owed, honor to whom honor is owed.

Says Wolterstorff: “Government is a servant of God. As a servant of God, it has a God-assigned task to perform. Its God-assigned task is to exercise governance over the public for the purpose of executing wrath or anger on wrongdoers, thereby indicating its support of doing good.”

He explains: “Paul is not saying that whoever occupies some position of governmental authority does so because God has put him in that position; he is saying that whoever finds himself in such a position, however that came about, has a commission from God, an assignment, to serve God by exercising governance over the public for the purpose of executing wrath on wrongdoers.”

Wolterstorff briefly notes the view of Aristotle, that the state aims at certain social goods, and is involved in cultivating virtue in its citizens – in making them good. This is referred to as a perfectionist view of the task of the state, whereas the view that Paul is promoting might be called a protectionist view: to protect citizens from being wronged. He writes:

The God-given task of government is not to pressure citizens into becoming virtuous and pious; its God-given task is instead to pressure citizens into not perpetrating injustice. Though it is not inconsistent with what Paul says to hold that government has the authority to seek various social goods, we should not fail to be struck by the fact that what he cites as the God-given task of government is deterring, punishing, and protecting against wrongdoing. God authorizes and enjoins the state to be a rights-protecting institution. This implies, as we saw, that it is also to be a rights-limited or rights-honoring institution.

Yes, there can well be a place for the state to do certain social programs, such as the building of roads and the collecting of rubbish. But that is not what Paul says is the chief task of civil government. The point of Romans 13 is there are limits to what the state can rightly do, and when it oversteps its God-given boundaries, then the believer can rightly disobey, especially when it seeks to clamp down on another important sphere of authority: the church.

This book was penned well before the past two years in which we saw blatant cases of government overreach and power grabs, and of the state directly impinging on the job of the church. But what he says is obviously relevant to our situation today: “The authority of the church places normative limits on the authority of the state. If the church has the authority to do certain things, then the state does not have the right to prevent it from doing those things. Should the state try to prevent the church from doing those things, it exceeds its authority.”

And when this occurs, there is a place for not submitting, and even for things like civil disobedience. Says Wolterstorff, suppose that my government…

…acts in violation of what justice requires. It directs me to wrong one of my fellows, or it deprives me of that to which I have a right and directs me to submit to the deprivation without resistance or protest. In such a case, there can be no doubt concerning divine authorization. God never has authorized and never will authorize the government to issue such directives. And if the government has no divine authorization to issue these directives, then obviously I have no obligation to obey such directives….

It’s not morally permissible for the government to direct me to wrong one of my fellows, nor is it morally permissible for the government to direct me to submit without resistance or protest to its wronging of me. It is on this last point that the theological account of political authority and obligation that I have derived and extrapolated from Paul’s discussion in Romans differs most sharply from traditional accounts.

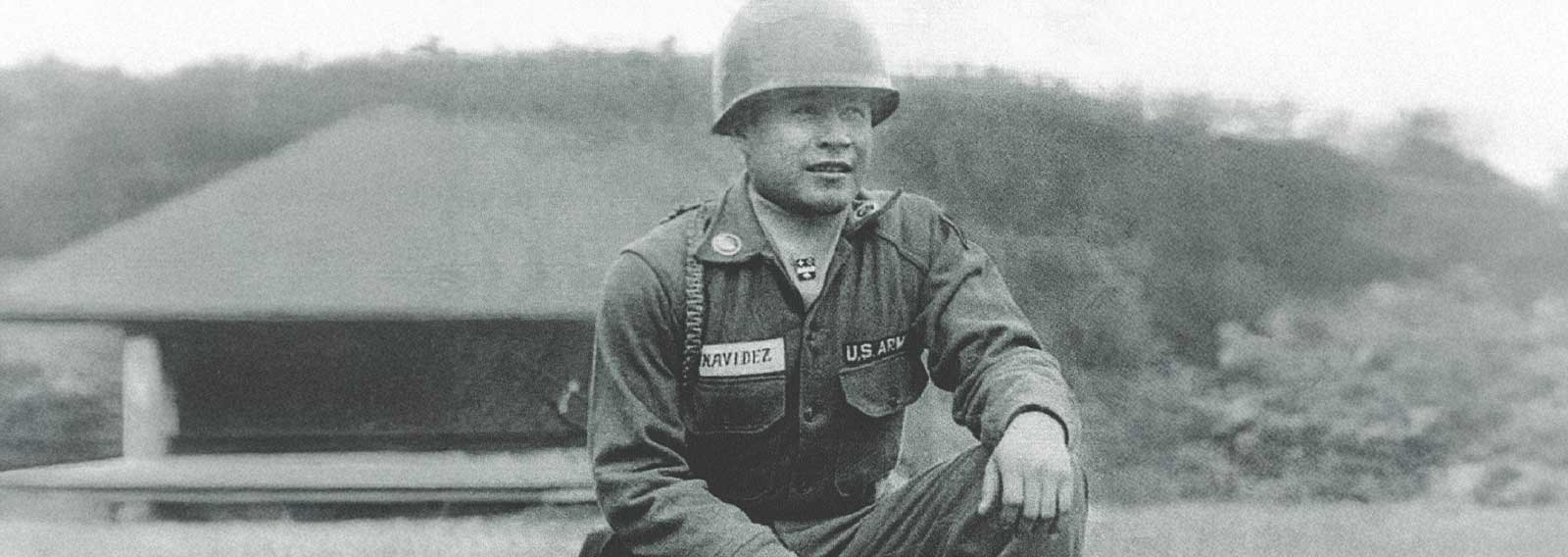

Given the whole of Scripture, this seems to be a much more accurate reading of what Paul has in mind in Romans 13. Indeed, there are numerous cases of God’s people resisting authorities and defying unjust commands and edicts. I have listed a number of them in various articles, including this one here.

In sum, the state is just one centre of authority, and God has set up others, such as the church and the family. The state is not absolute – only God is. Generally, we are to submit to the state, but only as it carries out its God-ordained powers. Beyond that, we can and should refuse to submit.