In the debate about whether we create or discover a writing voice, it doesn’t matter which side of the camp you land on. It’s generally agreed that a writing voice takes time to develop.

When I started a blog in 2013, I had no real idea how it would develop. My plan was to use the blog as a way of networking, and as a way of improving my own writing skills. In my post-graduate world, I wasn’t sure a blog would achieve either.

Looking back, I can see areas where I’ve succeeded, and I can also see areas where I haven’t.

In the areas where I haven’t succeeded, I can see one specific reason for it. I let a fear of being misrepresented by critics, influence how I wrote.

This stumbling block is illustrated by some of my earlier articles from 2013 and 2014. Those posts are unintentionally hard to read. Some were convoluted or weighed down by my attempts to navigate what Douglas Murray calls, the ‘dishonest critic’.

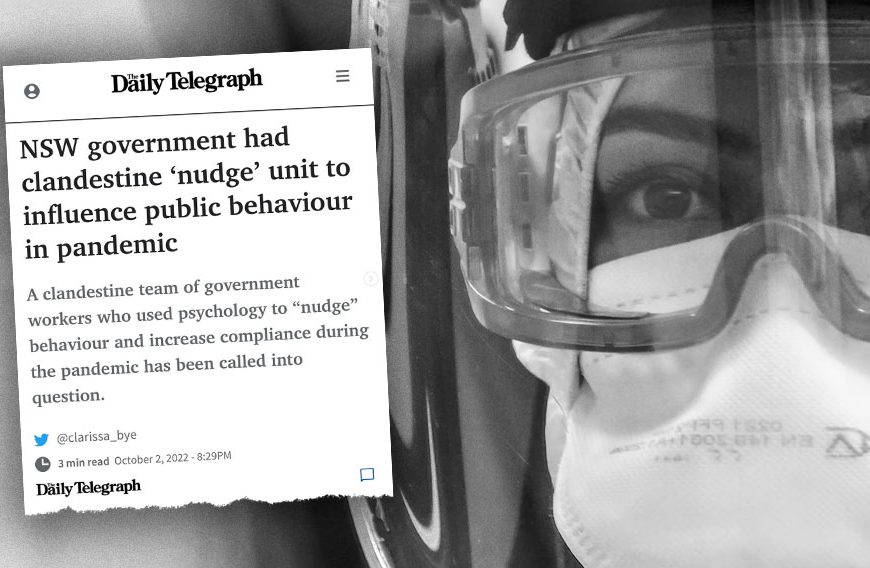

Overcoming this stumbling block has taught me how fear hinders free speech. Speech is paralysed through the fear of offending someone with the truth, or fearing that someone might deliberately misrepresent what has been written or said. Insecurity complicates intention. This fear messes up content, intention and limits the development of a writing voice.

Lindsay Shepherd recently made the observation that when we ‘try to answer a dishonest critic’ we fail to communicate effectively.

Citing Douglas Murray, she noted:

‘It’s hard not to sort of self censor in some way in this era, because everyone who’s a writer, speaker, thinker, or public figure is basically trained, (you train yourself or you’re trained) to learn, to write, or speak in such a fashion, that an honest person cannot honestly misrepresent you; that what you said is faithfully understood by decent people, acting in a decent manner. The era of social media, among other things, has caused something different to happen which is that many people are now, having to write, think, and speak in a manner that ensures that a dishonest critic, cannot dishonestly misrepresent you. There’s a problem with this: it’s not possible to do.’

At certain times in my life, I’ve found myself surrounded by ‘dishonest critics’. Criticisms from my parents, sister and some friends would sometimes include back-handed compliments. Along with snide remarks, criticisms padded with some half-truths, were designed to tear me down in order to pull others up. Sometimes these involved passive aggressive whip statements, and sometimes those criticisms were intense cross-examinations, where words were selectively chosen to steer an argument in a selfish direction; all designed to discourage, control and put down.

Growing up in this kind of environment has given me a greater appreciation for free speech and its consequences. Just as I can see the dangers in muzzling freedom of speech, I can see how some people would want to subdue it; force a straight jacket over it, and muzzle people from saying things that we disagree with or that can be harmful to us; such as the words of the ‘dishonest critic’ and their manipulative ways.

When it comes to creating content, writing and posting my own thoughts online, I was a clumsy beginner. I could have cried victim, for fear of the ‘dishonest critic’, and stayed there. Instead I’ve persevered, learnt some new things along the way, and made improvements.1

I don’t blame any one for my own clumsy writing, but I can acknowledge the root cause of it. Only then am I able to rise, and be raised above it.

Insecurity complicates communication. When we try to navigate the ‘dishonest critic’, how we communicate is bound in a type of psychological straight jacket. This breeds uncertainty. From uncertainty (self-doubt) comes insecurity and eventually silence. We end up saying nothing at all.

This why I believe, that the area in Western society where Jesus’ commands to ‘turn away from offence, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you,2 are most applicable, is freedom of speech.

Our response is our responsibility.

The Apostle Paul, in his Second letter to the Church in Corinth highlights personal responsibility in thought, deed and attitude, by encouraging Christians to remember that:

‘..the weapons of our warfare are not of the flesh but have divine power to destroy strongholds. We destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ…’ (2. Corinthians 10:4-5, ESV)

Paul’s statement, ‘we destroy arguments and every lofty opinion, taking captive every thought’ means taking personal responsibility for our actions. This includes how we use free speech and respond to the speech of others. In acting without fear of the bureaucrat, or ‘dishonest critic’, we deny those who would shut down freedom of speech, the room to stifle freedom, and complicate communication by forcing what we say through a bureaucratic tea strainer, like political correctness.

If we can relearn the Jesus-art of turning the other cheek, and recognise that words are only harmful to us if we let them have power over us, we don’t have to restrict, or stifle freedom by asking bureaucrats to police speech. As Paul said, ‘..the weapons of our warfare are not of the flesh but have divine power to destroy strongholds…taking every thought captive to obey Christ’.

This doesn’t mean ignoring the ‘honest critic’, making laws restricting freedom of speech, or refusing to take an assertive stand when wrongly accused, or misrepresented. What it means is that the freedom to speak, includes the freedom to listen, it implies room for self-limitation, and personal responsibility, because freedom of speech allows for honest rebuttal.

Jean Bethke Elshtain puts it this way:

‘Our ideas have to meet the test of being engaged by others, far better than having people retreat into themselves and nurture a sense of grievance, rage and helplessness…thoughts must be tested in the public square where you have to meet certain standards…we must be careful not to confuse tolerance with complete and total embrace…total acceptance does not mean universal love’ (Maxwell School Lecture, State of Democracy 2013).

Rather than limiting freedom of speech by advocating that free speech be forced through a bureaucratic tea strainer, perhaps we could keep this in mind. Even when ‘dishonest critics’, stand at the ready, with pen in hand, eager to pounce on any misstep, or easily misinterpreted statement, our response is our responsibility, their response is theirs.