The quote below, taken from Tolstoy’s ‘A Confession’, reads like a critique of the leviathan that is social media:

We were all then convinced that it was necessary for us to speak, write, and print as quickly as possible and as much as possible, and that it was all wanted for the good of humanity. And thousands of us, contradicting and abusing one another, all printed and wrote — teaching others. And without noticing that we knew nothing, and that to the simplest of life’s questions:

What is good and what is evil? We did not know how to reply, we all talked at the same time, not listening to one another, sometimes seconding and praising one another in order to be seconded and praised in turn, sometimes getting angry with one another — just as in a lunatic asylum.

Thousands of workmen laboured to the extreme limit of their strength day and night, setting the type and printing millions of words which the post carried all over Russia, and we still went on teaching and could in no way find time to teach enough, and were always angry that sufficient attention was not paid us. It was terribly strange, but is now quite comprehensible. Our real innermost concern was to get as much money and praise as possible. To gain that end we could do nothing except write books and papers. So we did that[i].

Of course, it is anachronistic to suggest that Tolstoy was talking about social media as we know it. Tolstoy’s words are, however, a critique of 19th Century, Russian media, its medium and the noise therein. Therefore, they are an early critique of the content and form which makes up a large part of social media. As such, they are a relevant criticism for us to take seriously, particularly when applying them to a 21st Century context.

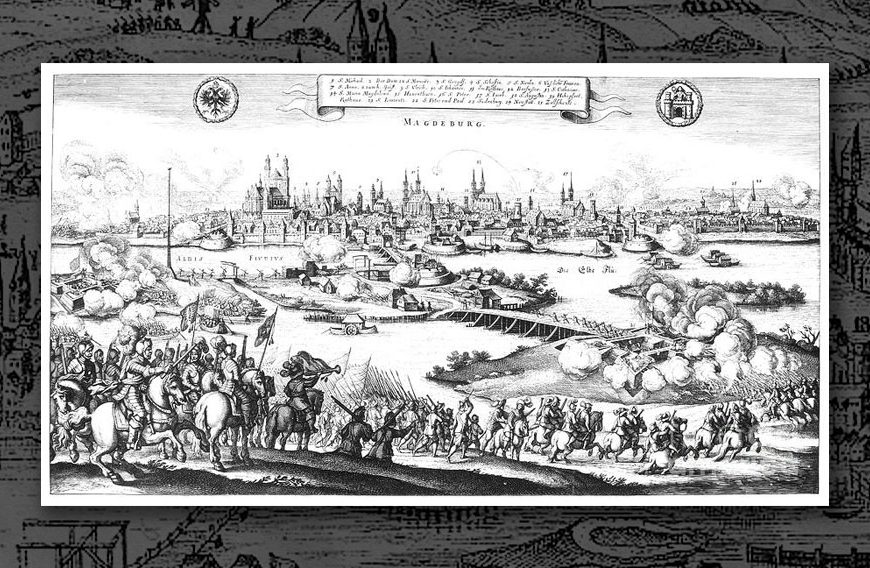

Henry Ergas from ‘The Australian’, made an interesting observation. In writing about sensitive information, how it is monitored, distributed and delivered. He provided a historical insight, which although topically unrelated, helps us to contextually frame the sharp poignancy of Tolstoy’s reflection:

19th century’s Pax Brittanica, was built on a solid technological foundation: Britain’s control of global telegraphy. As late as 1890, 80 per cent of the world’s submarine cables were British; Britain ruled the wires even more decisively than she ruled the waves… The sophistication of today’s communications networks is obviously many orders of magnitude that of Britain’s global telegraph system. In 2012, daily internet traffic was in the order of 1.1 exabytes, one billion times more every day than the 19th century system could carry in a year. And the growth rates remain breathtaking: wireless traffic alone is now eight times larger than the entire internet in 2000[ii]

If Ergas’ facts are correct, that is a lot of information being exchanged. For better or worse we engage, encode, disengage and decipher information at ‘breathtaking’ speeds. Matthew McKay suggests that ‘55% of all communication is mostly facial expressions’[v]. Thus, my conclusion is that because most of the information exchanged via social media is in written form, it seriously limits our ability to receive a message, in the same way it was intended to be received by the author. (there are many examples of how comments have been wrongly interpreted).

I consider Tolstoy’s reflection a full-stop. An important interruption that encourages us to take a breath and ask ourselves:

Is the information we are consuming authentic, well-informed, or is it just propaganda; distortion (noise)?

Further questions might be:

- Are we consuming information without really processing and retaining what it is being said?

- Who is saying this, and why are they saying it?

- Is the source trustworthy?

- Will my time be well spent reading this or not?

There is a further word worthy of consideration here. Augustine, in his day, had this to say about grace and human nature:

…many sins are committed through pride; but not all happen proudly. They happen so often by ignorance, by human weakness, and many are committed by people, weeping and groaning in their distress[iii]

Perhaps there is a timeless clarity by which these words help us to reflect on the interpersonal conduct, and content of the information exchanged on most prominent social media sites today?

Even with all its pitfalls, the strength of social media is in its ability to connect people and strengthen relationships. I remain a cautious participant of social media, aware of its limited ability to ‘properly allow a healthy and fair exchange of ideas’ (Elshtain, 2007). Therefore, I find here in Augustine and Tolstoy’s words, a reminder about the limits and the responsibility which coincides with the right to use such mediums. Augustine’s insight here could be bridged to Tolstoy’s reflection, and therefore buttress our proposition. Their words present us with a useful framework for a theological critique of social media.

If we look at Proverbs 4:20-5:6, we can see a parallel logic that could exonerate this train of thought.

Be attentive to God’s word, keeping them close. Guard your heart with vigilance, avoiding spin and smear. (“Refusing to be conned by the rhetoric of either the Right or the Left”)[iv]

Looking forward, ponder the path of our feet. Be attentive to wisdom. Use words that guard knowledge, and ponder the path of life.

References:

[i] Tolstoy, L. 1879 A Confession (Kindle for PC ed. Loc. 92-100).

[ii] Ergas, H. 2013 Wrong for Abbott to follow Obama and add lying to spying, The Australian, Sourced 25th November 2013

[iii] Augustine, ON NATURE AND GRACE (With Active Table of Contents) Kindle Ed. Loc. 704-706

[iv] Wright, N.T. 2013 Creation, Power and Truth: The gospel in a world of cultural confusion, SPCK & Proverbs 4:27

[v] McKay, M., Martha, D. & Fanning, P. 2009 Messages: The communications skill book p.59, New Harbinger publications