Are we fighting the postmodernists with one hand tied behind our backs?

Intellectual battles are the cognitive lifeblood of a healthy society. Life is complicated and the stakes are high, so thoughtful and passionate people have lots of arguments. Only by argument can we sort out the facts about complicated matters. Only by putting our ideas to the test of evidence and by being willing to change our minds can we make progress.

Intellectual fighting is not often fun, but it is better than settling our differences by physical fighting. The advantage of being an intelligent species, Austrian philosopher Karl Popper pointed out, is that we can let our theories die in our place.

But for argument to be productive, we need principles of civility to guide our investigations and debates. And we need our leading institutions—especially those like universities that are dedicated to truth-seeking—to make those principles explicit and foundational and instill them in the next generation.

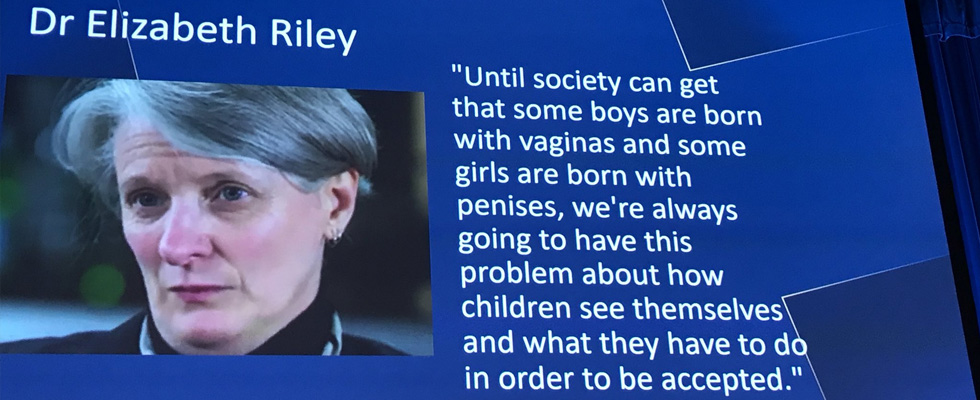

So we have a strategy-and-tactics problem: Postmodernists don’t fight by the same rules the rest of us do. When everything is subjective narratives, the subversion goes all the way down.

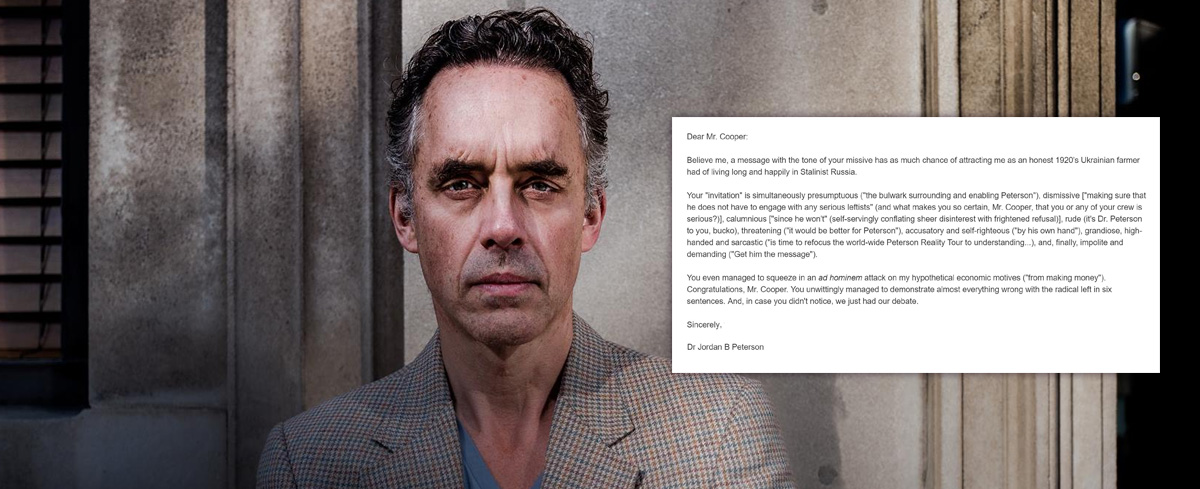

Our classic rules are: Approach discussion with a spirit of benevolence and give people the initial benefit of the doubt. Make one’s goal the mutual advancement of understanding. Hear out both or all sides. Be civil in criticizing and in receiving criticizing. Don’t make stuff up. Believe that truth matters.

But the postmoderns cast a jaded eye upon “truth” and see words as weapons in a battle between adversarial groups. In that battle, power is the only reality and “truth” is merely the most persistent or ruthless survivor.

American postmodern philosopher Richard Rorty put it this way: “Truth is what your contemporaries let you get away with saying.” (Source)

Rorty’s postmodern fellow-travelers in France, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and others work the same deconstructive territory.

It’s the difference between two lawyers arguing in a court over the facts and the best interpretation of them, their goals being truth and justice—and the lawyers who see the courtroom as a power struggle in which all that matters is who’s best at rhetorical and procedural manipulation.

Our code of ethics also includes rules about moral values: Be respectful legitimate differences. Tolerate an expansive range of beliefs and practices, unless physical force is initiated. Do not name-call or hurl insults easily. Be respectful of others’ accomplishments and proud of one’s own. Admit mistakes, individually and culturally, and strive to correct them.

On that latter point about taking responsibility: Individual and cultural improvement is a trial-and-error process, and while we have made great progress in battling poverty, slavery, racism, sexism, and incivilities, our historical record is not perfect. Hence the appropriateness of our intense debates, for example, over affirmative action and reparations. Can we make up for sins of the past? If so, how can we make good in a way that apportions blame and dessert fairly? Those are hard question, but morally responsible people take their history seriously.

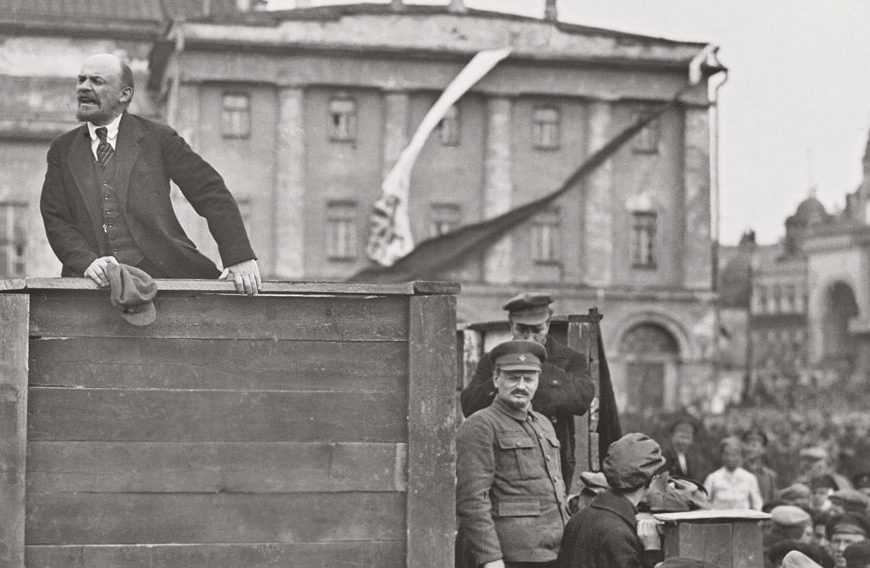

Here again Rorty represents the other, postmodern side. When asked directly about the Left’s many historical sins, crimes, and outright brutalities—and it’s important to note that all of the leading postmoderns are of the Left, usually the far Left—Rorty replied: “I think that a good Left is a party that always thinks about the future and doesn’t care much about our past sins.” [Source:“A Conversation with Richard Rorty.”]

(How unsurprising, then, that younger Leftists have little understanding of or care about the Soviet Union, China, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Cuba, or even Venezuela.)

I’m using Rorty as a foil, but it’s important also that he’s a mild postmodernist, one who—despite his philosophy of getting away with stuff and calculated forgetfulness—hopes that we can in limited ways still try to be nice to each other.

His contemporaries and followers in the next generation are not so nice. The nastiest insults fly at the drop of a hat. Fascist. Racist. Toxic sexist pig.

And that’s not only from the intellectual leaders themselves, or the graduated activists, but also from undergraduate students at now scores of universities across the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

There are no snowflakes, by the way, among the student activists. As young adults, they’ve watched scary movies, argued rudely with their schoolmates, had their hearts broken, learned about environmental degradation and the Holocaust, seen online porn, and in most cases lost grandparents and other loved ones. They may be young, but they’ve not been raised in bubbles. So when they call for “safe spaces” free from the expression of opinions they don’t like—more is going on than hurt feelings. When they hurl macro-insults against perceived micro-aggressions, a rhetorical weapon is being deployed. They have been trained well by their professors about tactics for shutting down opponents in the ideological wars. Delicate snowflakes do not use crude language and harsh confrontation.

So how do we deal with vigorous activists who are cynical about truth and civil debate?

In my upcoming Adventures in Postmodernism tour—in Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, and Brisbane—we will be grappling with exactly that question. How can the civilized deal with the anti-civilized without becoming themselves uncivilized?

For now, here’s an indication of the best strategy.

The first step is to understand what we are up against and where it came from. Bad philosophy got us into this mess, so philosophical self-education is essential. Clarifying one’s adversaries’ beliefs is empowering.

And that means grasping the fundamentality and audacity of the postmodern challenge.

Postmoderns are not merely those who believe that knowledge is hard, that truth can be slippery, and that goodness is rare. Every intelligent and thoughtful person knows that. So we can and should have vigorous debates among liberals and conservatives, optimists and pessimists, naturalists and the religious, objectivists and subjectivists, and so on, about the right or best answers.

But the postmodernists in theory and practice are a more dangerous phenomenon, for they make it clear that they are purely negative, purely critical, purely adversarial. Their interest is not in solving problems or suggesting improvements but rather in causing more problems and making things worse.

Here is Foucault himself: “These investigations are not intended to ameliorate, alleviate, or make an oppressive system more bearable. They are intended to attack it in places where it is called something else—justice, technique, knowledge, objectivity. Each investigation must therefore be a political act.” (Source:Eribon, 1991, 228)

Postmoderns reject everything important about our civilization, root and branch, as oppressive.

Note the key word of Martin Heidegger—in whose writings all the major postmodernists aresteeped—who argued that our entire Western tradition, from the classical Greeks on, must be subject to “Destruktion.” Andnote that a generation before Heidegger, Friedrich Nietzsche, another hero to postmodernists, argued powerfully that Western intellectual and cultural life had exhausted itself and that we were into an age of nihilism.

Oppression—attack—Destruktion—nihilism.

And since “Western” civilization is increasingly a misnomer as classical and Enlightenment values spread around the world, the stakes are truly global.

Yet the postmoderns know that we advocates of civilization are serious about our ideals of truth and justice and that we take pride in our great-but-imperfect progress. It’s precisely our seriousness and pride that the postmoderns aim to subvert—and to replace then with cynicism, self-doubt, and guilt. Hence the relentless charges of racial and gender and financial sin and the constant accusations of hidden, unsavory motives.

Understanding postmodernism is a start but not enough. We need action steps, as intellectuals and activists ourselves, as parents and educators, as business professionals and politicians. What do we do about postmodernism to defend and advance genuine civilization?

It’s helpful here to recognize that a nihilistic philosophy is uncreative. By its nature it is only destructive. It offers no truth, no goodness, no beauty, no creation of value. It therefore has to be parasitic on those philosophies that do generate positivity in the world.

That is to say that postmodernism depends on the very system it attacks for both material resources and moral status. So the action step is to take away the resources.

Jacques Derrida stated forthrightly that postmodernism was giving birth to “the formless, mute, infant, and terrifying form of monstrosity.”

We must starve the beast.

The most important resources postmoderns have are the ones we give them—especially our moral sanction. Moral sanction is a powerful psychological force. When we treat postmodernists as misguided idealists and as serious about problem-solving, we give them the standing that they in turn use to attack, often viciously, our sense of moral worth. And it’s always tempting to respond in kind.

The high road does involve costs. But we have advanced our civilization against amoral and immoral adversaries by taking the high road—in the hard work that created material prosperity, in the honest thinking that eliminated crippling diseases and doubled lifespans, in the righteousness of our vigorously attacking slavery, and the deep commitment to justice that extended liberties and equalities to men and women of all races and ethnicities—and doing so on the basis of a philosophy that strives for objectivity and often achieves it. We are the force for truth and goodness in the world. That is, we have the moral high ground.

It’s the postmoderns who have bought into a philosophy of pessimism and cynicism, who have given into jaded despair, and their attacks are meant to bring us down to their level.

We need to understand postmodernism, but we should not sanction it. Yet we can only remove our sanction because we know our genuine accomplishments and the ideas that made them possible. Know your enemy, yes, but first know yourself.