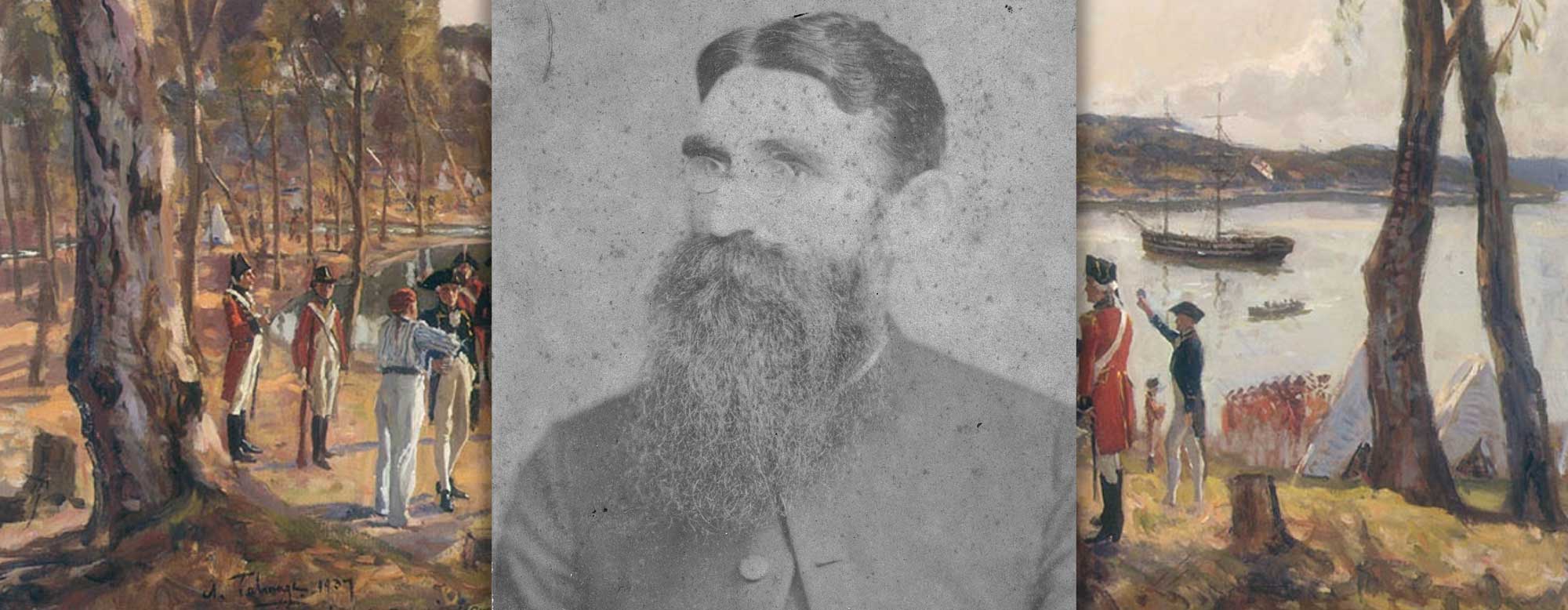

Rev John Brown Gribble was born September 1, 1847, in Cornwall, England. As a young man, the reverend moved to Australia, where he worked as a missionary among the indigenous people in New South Wales, Western Australia, and Queensland.

During his time as a missionary, Rev Gribble penned a book titled, Black But Comely: Glimpses of Aboriginal Life in Australia. In the book, Gribble explains that while early British settlers brought with them much good, they also inevitably introduced the natives to vices they would have otherwise been ignorant of.

According to the reverend, the impact was devastating:

Along with much which tends to honour God and benefit mankind, the European has introduced very much into Australia of quite an opposite character. With the noble institutions of England, which are the pride and boast of her children in the colonies, we have introduced its vices; and these exotic plants have taken deep root in the new soil, and have brought forth a terrible harvest.

The aborigines in their low moral condition came into the closest contact with these new and injurious influences; and they have gone down before them like snow before the rising sun. The vices which we introduced, which by our practice we recommended, and which they most naturally adopted, have sent them wholesale into eternity, and are rapidly mowing down the remnants of the race.

Consequently, laws were enacted in an attempt to prohibit the indigenous people from consuming alcohol. The laws were openly violated, however, and events such as those that follow became an increasingly common occurrence.

Intoxicating liquor is readily procured by the prostitution of the females; and scenes of debauchery that would shock the most abandoned denizen of Romeo Lane are of common occurrence.

The law prohibiting publicans from supplying drink to aboriginals is openly violated. Travelers through the towns indicated may at any time see numbers of aborigines with their gins (women) in an inebriated condition drinking at public-house bars, being as freely served as if there were no enactment against their being supplied. The police, for some reason known to themselves, never make the slightest attempt to prosecute, although the law is hourly broken before their eyes.

Many of the natives are afflicted with loathsome disease, the result of gross immorality. Surely some means can be divised to put an end to this frightful state of affairs. If the Government failed to perform its obvious duty some body of philanthropists ought to take the matter up and remove the scandal from the fair fame of the colony.

According to Rev Gribble, the reason why the indigenous population was so susceptible to adopting European vices was the “morally dark” state in which they lived prior to contact with British settlers.

Gribble describes their condition as “simply that of the savage – a savage of the lowest type.” According to the reverend, “as the lowest savages they lived, without clothes, without care, without trouble for temporalities, subsisting on simple products of nature without let or hindrance.”

“Morally, they were extremely dark,” Gribble explained, “so dark, indeed, as scarcely to possess any idea or conception of anything superior to themselves. Their chief supposition seemed to encircle the great Unknown, and of Him, the Great Spirit, they possessed a terrible dread. Their religious sentiment, if I may so express myself, was fear, only fear.”

Mixed with the vices of the Europeans, it was a concoction for disaster that was so severe, the reverend proposed the government establish mission station where the Aboriginal people could learn “the arts of civilized life, and receive instruction in the doctrines of Christianity.”

“Such stations,” Gribble wrote, “should be entrusted to the care of men known to be in possession of the essential qualifications for the management of such institutions.”

As Rev Gribble travelled, continuing his service to the indigenous people, he grew increasingly concerned about the state of native women and children, particularly those with “half-caste” infants.

Mixed-blooded children, abandoned by their white fathers was a major issue, according to Rev Gribble. And to make matters worse, when Aboriginal women gave birth to “half-caste” infants, mothers would either abandon the baby or the male members of the tribe would abandon them both.

I found them [Aboriginals] in a condition shocking to contemplate. I visited their camps; I entered their wretched bark and bough gunyahs. I went from place to place, and everywhere I met with the same wretchedness and woe.

In some instances, on making a first visit to a camp, the children ran away from me terrified at my presence; whilst their mothers—some of them, alas! only children themselves—cowered in their little dens like so many wild beasts, doubtless wondering what brought me to such a place.

In one camp I gleaned from the women that a tiny half-caste infant was concealed close at hand. I made a search, and by and by I discovered what I at first supposed to be a bundle of dirty rags stowed under some bushes, but on raising it I found it contained a dear little infant girl.

Oh! at that sight how my heart sickened and my blood warmed! Such helplessness, such woe, caused by the professedly Christian white man! And this case, I soon learned from good authority, and from personal observation, was, so to speak, but an index to a ponderous volume of iniquity existing throughout the colony in this very respect.

Rev Gribble recounts seeing a hundred-or-so “half-caste” children living in destitution, as wild animals and in desperate need of rescuing.

…these unfortunate children, many of them with well-formed and attractive features, and doubtless possessing minds capable of deep and thorough cultivation, are allowed to run as wild as the emu and kangaroo—and this state of things existing in a country which boasts a Christian Government, and whose churches contribute large sums annually towards the support of Missionary enterprises in far distant lands!

And again, quoting the Sydney Morning Herald, ‘I have recently visited some of their camps on Murrumbidgee, and found black women and numbers of their half-caste children in a state of the most melancholy destitution, deserted by the male members of the tribe; for I find that when the black girls are ruined by white men, so-called, they are then as a rule left to their own dread resources, without food, and nearly naked. And these poor creatures were at the mercy of every white scamp and vagabond. And what, I ask, is the consequence?

The up-rising of a race of wild half-castes in the very midst of a Christian community. And I speak within bounds when I say there are hundred of these young half-castes on the creeks and rivers of Riverina running wiles as the emu and kangaroo, with no idea of anything above or beyond themselves and their immediate surroundings. ‘Like brutes they live, And like brutes they must die,’ unless rescued by true Christian charity.

Aboriginal mothers and their mixed-blooded children, abandoned by both whites and blacks, were in great need of help, as the shocking incident detailed by Gribble below reveals:

On another occasion the keeper of a low bush hotel supplied the camp with drink, called in the white men around, and as an eye-witness informed me, ‘the scene was a little hell.’ The following morning I visited the camp, and there I witnessed a most revolting sight—poor old women and quite young girls helplessly drunk.

One poor young creature, with a half-caste babe upon her bosom, staggered towards me at my approach. I said: ‘What have you been doing, Louisa?’ ‘I have been drinking,’ she replied. ‘Who gave you the drink?’ ‘Mr. D–,” referring to the publican; and then, with the big tears streaming down her black face, she cried: ‘Oh, do take me away from this place. I don’t want to be a bad girl. I did not want to take the drink, but they made me take it.’

I said: ‘If you will wait till to-morrow I will bring a buggy and take you away,’ which, of course, I did, to the exceeding joy of the poor creature.

In one instance, Gribble describes coming across a campsite of eleven abandoned women and children. The reverend invited them to join him and his company. Their present condition was so bad, that “the poor creatures,” he said, “willingly undertook a journey of two hundred miles to escape the horrors of their camp life.”

The reverend had even allowed several of the young women to be cared for in the safety and comfort of his own home. All this time, Gribble said, the conviction grew stronger and stronger that he should establish mission stations for the well-being, safety and care of Aboriginal people, especially those women and children who had been abandoned and abused.

Gribble soon after established a mission station on the Murrumbidgee, and before long numbers of Aboriginal people began to flock to it for protection and care.

It was then that the poor waifs and strays in the district, hearing that the home was prepared for them, began to flock to Warengesda, our ‘House of Mercy,’ for protection and food. Our accommodation was small, and our means were slender, but seeing so many unfortunate women and children in a state of hunger and nakedness touched our deepest sympathies, and we were compelled to admit them…

As time passed on our numbers continued to grow, more natives came pouring in from all quarters—from the Darling, the Lachlan, the Murray, and even from the distant Naomi. Hearing that there was a home for the black on the Murrumbidgee, they came to see for themselves, and although some returned, many decided to remain.

Rev Gribble’s account reveals that early Australians, both white and black, were guilty of abandoning their young ones on the basis of their skin colour. But this is more than a skin issue, it’s a sin issue. What we ought to acknowledge in this is not only the universal sinfulness of humanity but the power of Christianity to overcome that sin.

It was Christianity that compelled Gribble to travel to Australia as a missionary to the Aboriginal people. It was Christianity that caused Gribble to view the indigenous Australians as equals, deserving of respect, care and kindness. It was Christianity that prompted Gribble to establish mission stations for the well-being of abandoned women and children. And it was Christianity that radically changed those women and children for the better.

Take the accounts of an Aboriginal woman named Eliza Nelson and the little girl named Johanna, for example:

Eliza Nelson, a pure aboriginal, was, when I found her in the camp, a most pitiable object; but under Christian training she soon exhibited some most attractive traits of character. First of all she was led to see herself a lost sinner. She showed every sign of a true repentance, and then there followed a simple trust in Christ, which she never again lost. I saw from the first that she was very delicate.

Consumption, the dread enemy of our blacks, claimed her, and she rapidly declined. A few days before she died her sister came to be to say that Eliza was very ill, and would like to see me. I found her surrounded by weeping friends. She was having a hard struggle for breath. I said: “You are very weak, Eliza. Have you any fear of death?” She replied: “No, because Jesus is with me.”

“The Lord Jesus,” I said, “is always near those who put their trust in Him, and especially those who, like you, are passing through the dark valley.” Clasping her hands, and with a look full of meaning, she said: “I know that, sir, I know that.”

On the night of her death she sent for me. I hastened to her bedside and found that she was indeed passing away. I poured into her ears portions of the Divine Word, which I knew she loved. She was unable to speak, but enjoyed perfect calm and peace.

Her little boy stood by her side, and to him she had said just before I arrived: “Harry, I am going away from you to Jesus; I want you to be a good boy. Give Jesus your heart; serve Him, and then when you die you will meet me in heaven.” Thus Eliza Nelson, one of the first fruits of our Mission, was gathered to the eternal home.

Johanna:

Johanna, a little black girl, about twelve years of age, came with me to the Mission station from a place called Cootamundra, about one hundred and fifty miles away. Though her skin was very black, her heart seemed pure and tender, and soon yielded to the touch of the Saviour’s love. Very earnestly she listened to “the old, old story,” until the love of Jesus became to her a great reality. She opened her heart to Him; He entered, and dwelt there.

One evening, after service, I was walking to the Mission-house, when I heard the familiar pattering of bare feet behind me. Looking around, I saw the little girl. “Well, Johanna, what is it?” With a great deal of native shyness she replied: “I would like you to baptize me, sir.” “Why would you like me to baptize you?” I said. “Because I love the Lord Jesus, sir, and I want to show my love to Him before my friends.” Tears came to my eyes at these touching words, and I said: “All right, Johanna, I will baptize you;” and one Sunday shortly afterwards the dear girl came forward, in the presence of the whole of our Mission community, and in the holy rite of Christian baptism made her profession of faith and love.

Only a few weeks afterwards Johanna’s pure and loving spirit passed away from “our home of mercy” to join that “great multitude” before the throne.

It was my sad duty to prepare the coffin, and to place the little wasted black form therein; but amid my tears, joy filled my heart to overflowing at the thought of this precious gem, the glorified spirit of our dear little Waradgeri girl, shining in beauty in the Saviour’s crown.